1976 When Santorini was remote, welcoming, and cheap

(long read)

There was at time, not long ago, at least in the six thousand years of human settlement on the Greek island of Santorini, that I and my roommate were the only two people sitting on a stone bench in the town of Fira watching the sun set over the Aegean Sea.

I can’t be certain of the exact date, but it was most probably October 1, 1976. That was a time when Santorini was remote, welcoming, and cheap. Remote, largely only accessible by ferries where Santorini was the usually last call on a voyage through the Cyclades, ships which called first at islands such as Ios, Mykonos and Paros. Welcoming, there were not that many tourists and the people of the island were more than friendly and always helpful. Cheap, especially for backpackers. There was only one hotel for the better off tourists, but many rooms available, mostly in small buildings adjacent to the proprietor’s home and a less than 10-minute walk from the cliffside overlooking the sea and the tavernas that lined the street.

n

Forty-eight years later it is now almost impossible to see that tranquil sunset. There are just too many people cramming into crowds to try and see the sun go down over the caldera of the volcano. According to media reports and photographs, if someone were at the back of the crowd, they would see nothing, but a forest of selfie sticks and arms raising mobile phones. Tables at cliffside restaurants are at a premium.

It was last week that the world’s major media, including The New York Times, The Guardian and Britain’s Daily Express, rightfully pointed to Santorini as a prime example of the overtourism plaguing the world’s most popular destinations.

Now Greece’s prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotaki, has announced measures to bring down the numbers, including increasing landing fees for cruise ships, an increase in the lodging tax paid by hotels and short-term accommodations and a curb on new construction on the stressed-out islands.

That news coverage brought back my memories of my first visit to Santorini. So, I looked out my Kodak Ektachrome colour slides and scanned them to show what the island was like when I visited forty-eight years ago.

More pictures on my photography site My visits to Santorini in 1976 and 1981

Watching the sunset

When I did my post university backpacking trip to Europe in 1976, Santorini was high on my list of must places to visit, alongside Hadrian’s Wall, Viking Denmark and Norway, Rome, Athens, and Delphi. I had been nuts about the ancient history of all cultures at least since I was eight or nine years old. I was intrigued by the then new contention by archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos that the island of Santorini, also known by its ancient name Thira or Thera, could be the origin of the legend of Atlantis based on the catastrophic volcanic eruption around 1600 BCE. and the archaeological studies of the once thriving town now called Akrotiri (after the nearest village.)

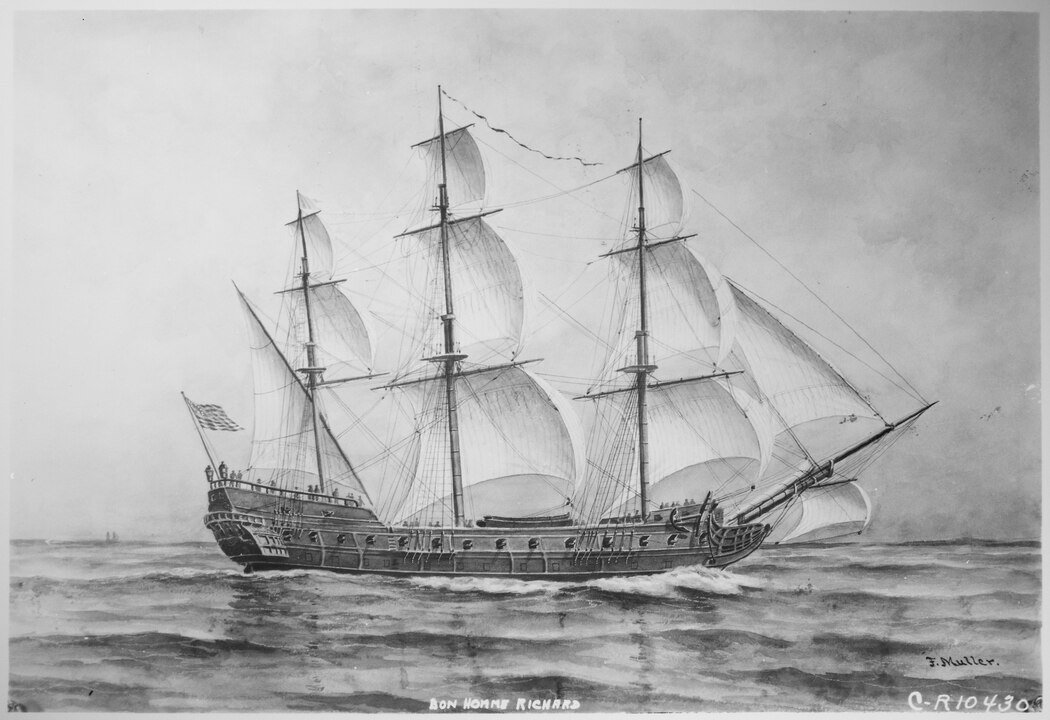

The trip from Piraeus to the islands was very rough with fierce winds and heavy waves rocking the ferry. The knowledge at the back of mind that this was a late September clear weather north to northwest fierce meltemia or Etesian winds, that they were same winds that probably drove Odysseus off course was no consolation. It was one of the very few times when I was on a boat, large or small, that I actually got seasick.

By the time the ferry reached Santorini, the seas had calmed, the meltemia winds begin to die down once the sun sets.

It was night. Then there were two ways to get up from the ferry docks in the old port of Skala below the town of Fira. Men were waiting with donkeys to carry the older and less adventurous tourists up the stairs along the cliff face to Fira. The rest of us climbed the hill with our backpacks (of course). (There is now a ferry port at Athinos 10 kilometres to the south.)

When I and the others were about halfway up, we met back packers heading down to the ferry. “Don’t eat at the taverna between 5 and 7, wait til the sun sets.”

“OK” I thought. At the top of the hill, women were waiting for the backpackers to rent rooms or houses.

One woman had a small house attached to her home, with two beds. She looked at me and then pointed to another backpacker, a blond guy about my age and offered the two of us the room.

The Guardian reports that in 2024 Santorini has an estimated 80,000 hotel beds, more per square metre than any other Greek tourist destination apart from Kos and Rhodes.

I don’t remember seeing him on the ferry. He was from Germany, also back packing and spoke excellent English. We spent the few days hanging out together, except when I went off searching for archaeological digs.

There was a taverna at the caldera cliff road overlooking the sea. That is where we had breakfast.

We decided that we would follow the advice of the departing backpackers and not have supper until after seven o’clock.

We soon found out why. It was at five that a cruise ship came into port. The donkeys and their drovers were ready to bring the cruise ship passengers up the cliff steps. That was when the taverna raised its prices to the tourist menu and the shops stayed open to sell souvenirs.

With nothing else to do, my roommate and I sat on that stone bench to watch what is now the famous “flaming” sunset. (I lost the note pad with his name and address in Germany many years ago). The funny thing was that along with the sun set, we also became a tourist attraction.

At least three and maybe four people from that cruise ship took our picture, along with the sunset. I remember one woman asking us to turn to her and “smile.”

I keep wondering if somewhere, in the United States, since most of the cruise ship passengers were Americans, there could be in a household’s photo album taken by their parents or more likely grandparents or even great grandparents of two “hippies” watching the sun set on a Greek island.

The cruise ship passengers departed by donkey. The prices in the taverna went back to “normal” and the backpackers, tourists and the locals came in to have dinner.

There were probably no more than a hundred or so tourists who came off the ship to take a couple of hours to see the sights of Fira. A cruise ship in 1976 was a fraction of the size of today’s giants.

Media reports say that the Hellenic Ports Association reports that 800 cruise ships brought in 1.3 million visitors to in Santorini, who were a major source of foot traffic: a portion of the nearly 3.5 million visitors in 2024 to an island of 15,500 year-round inhabitants.

In an interview with The Guardian, the mayor of Santorini, Nikos Zorzos called for urgent action to stop a construction spree that risks spurring the island’s ruination.

“We live in a place of barely 25,000 souls and we don’t need any more hotels or any more rented rooms,” he told the Guardian. “If you destroy the landscape, one as rich as ours, you destroy the very reason people come here in the first place.”

The building boom is related to the record numbers visiting an island that had already reached “saturation point” before the Covid pandemic, Zorzos told The Guardian.

There were only a few tourists on those sunny early autumn afternoons in 1976. Now photographs form the wire services like AFP/Getty and Reuters published in the media show streets so crowded that people have trouble moving.

The Blacksmith

When I had arrived in Greece, on the ferry from Brindisi to Patras, I had taken an express bus to Athens. When the bus arrived in Athens, the surly bus driver roughly pulled all the luggage out of the bus, without much care and attention to anyone’s bags.

When the driver pulled my backpack out, it somehow got caught on the edge of the luggage compartment and snared. One of the rings holding the pack to its frame was pulled off. He then tossed the backpack on the ground with the other luggage.

I hadn’t really needed the backpack when I stayed in Athens or when I took the ferry, but I had more traveling to do.

On my walk around Fira, I noticed a blacksmith working at forge, something I didn’t expect to see in 1976. On the chance that he could help me, I took the backpack to his shop. With gestures I showed him the broken ring that attached the backpack to the frame. He smiled, nodded, and pulled out an old nail from a box. With the deft and speed of an expert, he first used a chisel to cut off the head of the nail, then took his tongs and quickly curved the old nail partly around the horn of the anvil. Then he took the nail, pushed it through the eyelet of the backpack and the hole in the frame and closed it with the tong. I offered some money, but he shook his head, smiled, and sent me on his way.

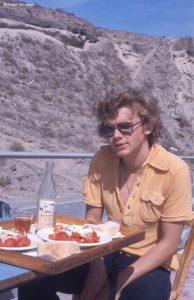

Tomatoes and wine

I am sure that the food on Santorini could be just as good as it was 48 years ago, but even in a place that attracts tourists form around the world, one wonders how much of the food is still really “local.”

Again, to quote The Guardian, About a fifth of the southern Aegean Island has already been concreted over. But to the consternation of ecologists, authorities in Athens approved even more building permits between 2018 and 2022, enabling construction on an additional 449,579 sq metres of terrain – about 2% of its 76 sq km (30 sq mile) total landmass.

Santorini’s volcanic soil and climate is perfect for two juicy fruits. Grapes and tomatoes. The best Greek salad, with the juiciest tomatoes I have ever tasted in my life come from Santorini, which grows both the local variety of Santorini cherry tomatoes a and regular tomatoes. The grapes are equally delicious and produce fine dry white wines and sweet dessert wines. The Santorini wines were so famous, according to Wikipedia, that the Ottoman Turks, exempted the island from the Islamic prohibition against alcohol. The Russian Orthodox Church adopted Santorini wine for the eucharist. I was told when I was there that best vintages were reserved for the Czars.

Earthquake and recovery

Santorini suffered a devastating earthquake on July 9, 1956, estimated at between 7.5 and 7.7 magnitudeand a 25 metre tsunami. At least 53 people were killed and more than 100 were injured. 35 percent of the houses collapsed, and 45 percent suffered major or minor damage.

Santorini was just beginning to recover 20 years later in 1976. I could see then what appeared to be damage left over from the earthquake.

The airport was built in 1972, and I was told when I was there in 1976 that the people were hoping that the airport would bring in more tourists. It was expanded over the years and as of 2021, is capable of handling Boeing 757 and 737 and Airbus 320 jets.

Santorini did not have an electrical grid until 1974, two years before I arrived.

In April 1984, Robert Stock, then a senior editor with the New York Times Magazine, visited Santorini. Stock wrote “take tourists in their stride. They are happy to exchange smiles, to wait on you in their shops and restaurants, to welcome you to their festivals. But they have their own lives to live. After a few days there, you relax.”

Does anyone relax there in 2024?

One of the points of Stock’s report was that in 1984 was that 18 years after the earthquake and tsunami, the Greek government was funding restoration and building on the island, not just to help Santorini recover ( the rebuilding program was also on other islands) but “to channel foreign visitors away from overcrowded Athens and out into the hinterlands, where they can enjoy a taste of village life. “

“Mass tourism really took off in the 1990s and that’s when you began to see change,” Zorzos told The Guardian.

In 2024, the Times reported that it was not just Santorini that was overcrowded but Athens as well “The influx of tourists this summer put Athens under tremendous strain as it grappled with excessive heat, as well as water shortages. Wildfires, which broke out across Greece, have engulfed the forests in the Attica region, even spreading to the suburbs of Athens…

Protests against overtourism flared in Athens in July, with “No tourists” graffiti emblazoned on buildings and residents calling for measures against vacation rentals, which they say are taking over entire neighborhoods.”

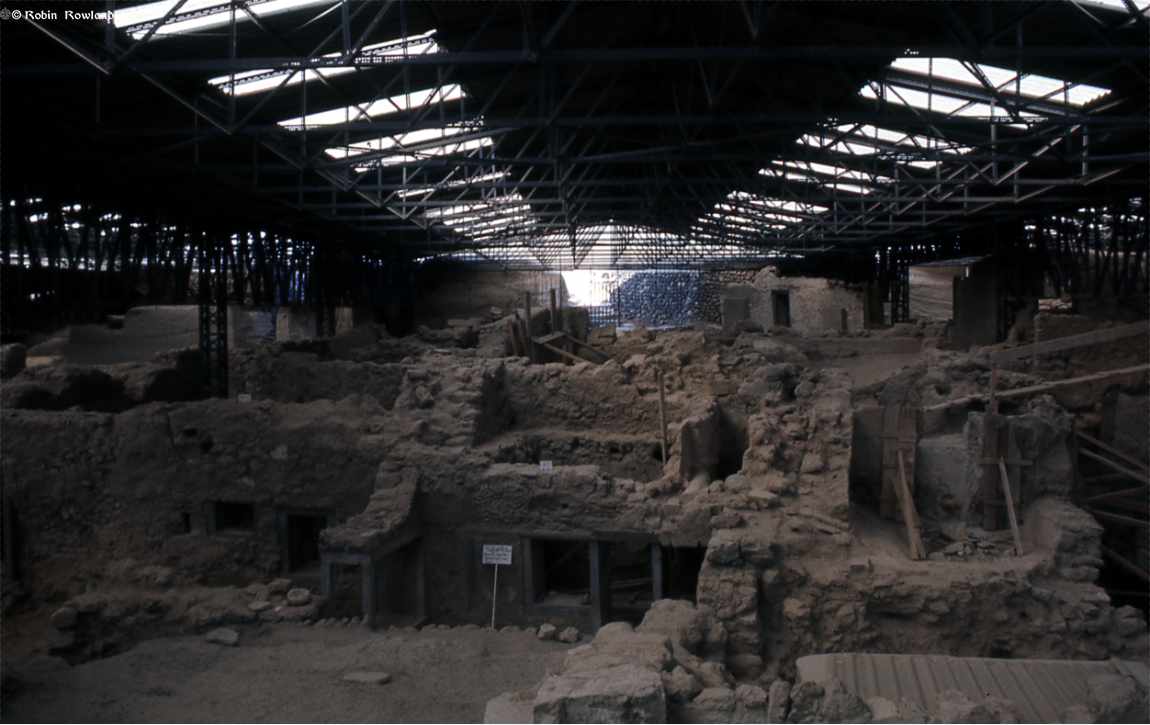

Akrotiri

Back in 1976, I took a day trip to the east coast, first to walk through the ruins of Akrotiri. I had been at Pompeii just two weeks earlier. In both places, thriving, vibrant towns destroyed by nature, you walk the streets, pause at a door or a window and wonder who the people were who lived in that house. It is likely that the population of the town evacuated after the earthquakes that preceded the eruption. Whether they found safety is unknown, but chances are high that they did not survive the eruption and tsunami.

The formal excavation had begun in 1967 and most of the preliminary work was reparing the site, so only a portion of what tourists see today was uncovered when I was there in1976.

You can still walk the streets as I did in 1976. In 2005, a new roof to replace the original was under construction collapsed, killing one visitor. The site was closed from 2005 to 2012 while a better and more robust shell was built to protect the site. There is now a raised walkway for visitors to view over the site and a specific path through the streets. Archaeological work did not resume until 2016. In 1976, you could just show up, marvel at the bronze age town, and take all the time you wanted. Today with the crowds timed tickets are recommended.

Kamari Beach

My next stop was the now famous Kamari beach which isn’t far from the Akotiri site. The Kamari beach is known for its black sand. As you tell from my photograph, there were probably no more than a dozen people there the day I visited, even though the early October weather was sunny, clear, and warm, as you can see from the sunbathers. Today, the tourist sites say, “Kamari is fully organized, offering a wide range of facilities like sunbeds, umbrellas, and various types of water sports.”

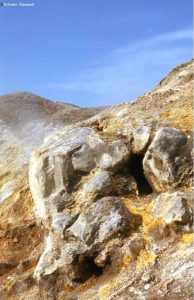

The Volcano

My roommate and I took the tour to the volcano. The caldera itself is mostly submerged after the catastrophic eruption and explosion three thousand years ago. The main volcano is on the island of Nea Kameni. In 1976 and today boats are available from Fira that not only allow you to hike to the volcano but tour the harbour area as well.

It is and was about a thirty-minute hike from the dock to the crater and back along a well-worn path through the rough gravel and sharp rocks that had broken off over the decades.

Once you got to the crater itself, you could smell the sulphur and see the rocks stained bright yellow. One interesting difference is that contemporary photographs show yellow flowers growing along the trails. My photographs show no plant life in the same area. What I did spot was a lizard sheltering from the sun under a rock.

Among the changes at the volcanic island today authorities note “Any rubbish should be discarded directly in the designated bins.” There were no rubbish bins in 1976 and one thing I noticed that in one of the depressions off the trail, scattered about were yellow Kodak cardboard boxes that held film cannisters. I would guess that one fool dropped a box and as litter is contagious, other people did the same. Now the problem is, as the same guidelines warn, “Observe safe distances and settings for selfies.”

We took the boat back to the port and once again climbed the stairs. (Today’s tourists have the luxury of a cable car from the port to the town. )

Unlike the night we arrived, it was the heat of the afternoon and as soon as we got to the top, we headed straight for the taverna. If I drink beer, I usually sip and nurse it. The afternoon I chugged a whole bottle of Amstel. Then I ordered a second Amstel and finished it in about another ten minutes.

The moon and Orion

I was running out of money, and I wanted to see Delphi before I returned to Canada. I had a flight booked on Icelandic (the backpackers’ airline in that era) from Luxemborg to New York to get me back to Toronto for Canadian Thanksgiving.

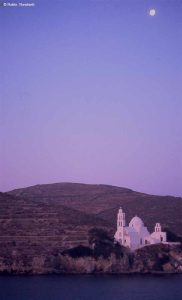

My roommate was going to stay another couple of days, but I headed down the steps to the ferry docks for the overnight trip to Piraeus. The ferry left as the sun was setting and I captured a shot of the waxing moon over a small waterfront church as the ship left the island.

Unlike the trip to Santorini, the sea was calm, the sky was clear. I spent most of the night on the deck, watching Orion rise over the Aegean, and thought again of Odysseus and the other sailors who must have seen stars from the deck of their small sailing ships all those thousands of years ago.

On October 9 or 10 I watched the full moon rise over the Tholos of Athena in Delphi and then began the long trip back to Toronto. Delphi was much more expensive both for simple accommodation and meals than Santorini had been. But, of course, Delphi has been a tourist trap for most of time going back to at least the sixth century BCE.

I returned to Santorini briefly in September 1981. The island was still welcoming. When I rented a moped to go to Akotiri and stopped to the photograph the grape harvest, one of the farmers came over and gave me a bunch of delicious grapes. The island was just beginning to change. Where the blacksmith shop had been there now appeared to be a disco with a coloured lights around the entrance.

Changing world

In 48 years, the world has changed. A couple of years ago, I talked to a young man just back from his own post university trip to Europe. He stayed connected with family and friends by phone, email, and social media. He was never disconnected from home.

Today the younger members of my extended family post their travels on social media with minutes of taking a photo with a phone.

In the post Second World War era from 1945 to the mid-1990s, if you were a young traveler, backpacker or temporary worker or all three, carrying guide books including the one that began as Europe on $5 a Day (imagine that) or Harvard’s Let’s Go, the student guide to the world, (which lasted until 2019 and closed during the pandemic) you were often on your own for the first time. International phone calls were expensive, except in emergency. You loaded up with American Express travelers’ cheques. You picked up your mail (including, you hoped, money from home) at an American Express office or a “Poste Restante (General Delivery).

Whether the management of American Express imagined it, serving young travelers and wondering exiles was one of the best long-term investments the company made, it is highly likely that everyone of them living today has an American Express card.

Your family heard from you with occasional postcards and letters and hoped you were doing OK.

For the centuries and decades prior to the millennium, for those who could go on a trip it was often the now cliched heroic journey. The other cliches finding yourself or becoming an adult are cliches because in reality those journeys were important to people’s lives.

It wasn’t always confined to the rich and privileged. Even those who not to well off or even poor found a way if they were determined to travel.

There was the vision quest in numerous cultures and societies that supported such quests.

Rich and poor in all religions and most especially the monotheistic religions went on pilgrimages.

The European aristocratic rich had the grand tour.

With better transportation in the 1920s there was the best selling, popular horizon chasing American (and secretly gay) writer Richard Haliburton. Ernest Hemingway, Morley Callaghan and others “found themselves’ and wrote in Paris. James Baldwin also went to Paris in a self-imposed exile from American racism. There were many more.

So now I am this old guy sitting in his home office, with “Those Were the Days My Friend” echoing through his brain. Those days were my “good old days” (of course other parts of the 70s and 80s weren’t so good).

I must wonder; however, how much Generations Z and Alpha will be able to experience that freedom of being on their own, exploring a world? They have been tied to screens from the moment they could toddle and now no matter where they are today their lives are controlled by addictive algorithms created by high tech.

I hope that at least some of them can in their young lives be able to do what I did, sit on a stone bench, and watch a glorious flaming sunset without a couple of hundred people crowding beside and behind them, busy trying to take a selfie.

That’s because with the climate crisis and all the economic and political turmoil in the world, their “good old days” may be worse for their children or grandchildren on a dying planet.

The crisis of overtourism

As travel has rebounded from the Covid-19 pandemic, the word “overtourism” has moved from the concerns of few activists even before Covid-19 to the front pages and screens of the world’s major media.

The Guardian reports Flight shame is dead’: concern grows over climate impact of tourism boom.

Here in Canada, the CBC reports that Has Banff National Park reached a tourism tipping point? and Nighttime nightmares grow for stargazing spots.

Overcrowding, bad behaviour and nocturnal roadkill prompt new rules

Travel has rebounded since the end of Covid-19 lockdowns and travel restrictions at a time when the planet is under increasing stress. As the Guardian points out increased jet travel means more greenhouse gases. Banff National Park is plagued with increased traffic and is now restricting private car access to some areas.

One of the so-called “influencers” saw no problem at all about renting a car on Santorini. Why would anyone, especially someone young and looking to the future with a looming climate crisis, rent a car on a small island with lots of tour buses and guides who are local and deserve the employment? This aging curmudgeon got along fine on Santorini on foot, by bus and by moped. (To me, unless someone has a physical challenge, or you are in an area where a car is essential for a longer journey, unnecessary car rental just adds to the overtourism crisis. I would note that the influencer and other travelers added to their carbon footprint by flying or taking a ferry, or both as did I unknowingly back in the day.)

Overtourism is a dilemma because overtourism is tied to the rest of the world’s problems. Despite what some demographers claim, humanity has reached the carrying capacity of planet Earth. It is not just humanity encroaching more on the natural world. Nor is just the increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere which is fueling fires, droughts, heavier rain, and stronger storms. Nor is it just the biodiversity and extinction crises.

Despite a vibrant economy there are fewer good jobs especially for the young in both the developed and developing world. The outlook for those jobs is increasingly poor as Artificial Intelligence destroys more jobs than it creates. Neoliberal economics with its emphasis on shareholder value has been cutting jobs and relative wages and increasing work life pressure for more than 40 years. The cult of tax cuts has led to the decay of infrastructure and social supports until little is left and the conservatives still in the cult believe that cutting taxes even more will somehow make things better. There is a housing crisis across the developed world and in the developing world, overcrowded cities, soon to be megacities.

Around the world the now Airbnb monopoly has increased the opportunity for people to travel while clearly destroying available affordable housing for local people in every country that it operates as well as increasing the number of tourists in a location. And like the rest of the High Tech from Silicon Valley, Airbnb has made things worse not better. It’s a must use monopoly and that means that all the former BnB or vacation cabin booking sites are long gone and when you travel, you are forced to deal with Airbnb, just as Amazon and Google are silicon monopolies.

What does all mean? Stress, increased stress. Back in the early 70s when there were dire predictions of a population catastrophe there also prediction that human beings would react like overpopulated rat colonies. We are not there yet but we are getting closer to those rat colonies. It is not just stress from the environment, employment, and housing problems it is stress from a world with wars, political turmoil, and threats to the few remaining democracies. People just need to get away. People crave vacations.

Travel can also open perspectives to different peoples, cultures, and experiences. That is if travel is done properly. That change in perspective becomes more important today as much of the world, while millions still travel, seem to be withdrawing from that world into nationalistic and nativistic bunkers. There is also no perspective if a tourist is in a fly in fly out cocoon where they never leave their own culture or as is today everything is so crowded that perspective is impossible.

It is highly likely that more and more locations will either limit the number of visitors either to an island like Santorini, a city like Venice or a specific location like Rome’s Trevi Fountain (which was busy but not crowded when I visited in 1976) or charge increasingly higher fees to enter or both.

It is still largely the relatively well off who travel the most, The Guardian reported that in the UK, for instance, 15% of people take 70% of flights, while about half the population do not fly at all each year. The same report says that on a global scale and the distinction between the two groups begins to blur. More than a century after the first commercial flight took off in 1914, researchers estimate that less than 5% of the global population flies abroad each year.

Another Guardian article reported that although it may be tempting to see the visitor cap as a possible answer to t e overtourism crisis, experts are quick to dispel the idea. They argue that while limiting visitor numbers may work in the [the Spanish island of] Cíes, it will do nothing to address the issues that have been fuelling protests around Spain and beyond.

“If we try to put caps on the number of people entering a city – as they’ve tried in Venice – then you end up turning the city into a theme park,” says Claudio Milano, a researcher at the University of Barcelona’s social anthropology department.

“What you’ve got in the Islas Cíes and in Machu Picchu and in these big national parks is something that works in parks, where we need careful capacity because of the environment. If you do that in a city, then the message you’re sending out is that this is a theme park.”

Milano says this year’s “domino effect” demonstrations in mainland Spain, the Balearics and the Canaries show the extent to which tourism has become a focus for socioeconomic and political grievances and anxieties.

“We need to remember that these movements are anti-touristification and not anti-tourism – that’s the key and the big difference,” he says. “More than this being a turning point, it feels like a moment when tourism has become politicised in different contexts.”

It’s politics and all politics is local.

Neopuritan holier than thou demand

s for restriction seldom work, they just get peoples’ backs up (as unfortunately the Covid-19 restrictions and vaccination campaigns crucial to saving lives proved).

All these problems are interrelated. Difficult to solve.

I grew up in a era that is called a “Golden Age” when all the science fiction writers, right-wing, conservative, liberal, socialist or whatever political stripe, part of the Greatest Generation, many of whom served in one way or another in the Second World War, assumed that if the planet was faced by an existential crisis like the looming climate catastrophe that just as in the war, the Great Depression and the Space Race, most of the world would unite to face that crisis.

The opposite is happening. The crisis is made more worse as conservative and authoritarian politicians deny that these problems exist and promise a fantasy return to a past that never really existed. More of these politicians are gaining power in the current anti-incumbent climate.

One last old boomer curmudgeon note. Perhaps the overtourism is a symptom of something deeper. More than a Covid rebound. We’ve seen it in some more recent apocalyptic science fiction movies and books. Enjoy yourself while you can because the world is going to total shit. As the old saying goes “Eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow you will die.”

I can only hope I am wrong, and that Generation Z and Generation Alpha will look back to the Greatest Generation, come together and fix things.

For more about overtourism I highly recommend the podcast End of Tourism, produced and hosted by Christopher Christou (disclosure Chris is my nephew. However this podcast delves deep into the issue)

My visits to Santorini in 1976 and 1981 - Robin Rowland Photography

[…] Much of the world’s major media have reported that the beautiful Greek island of Santorini is a prime example of overtourism n 2024. That pronoted me to write a memoir of my visit first in 1976 When Santorini was remote, welcoming, and cheap. […]