“A point far off in imaginary space.” In 1970, two books tried to predict 2020. How right were they?

Fifty years ago, in 1970, two books, one written and edited in the United States, the second in Canada, both gathered prominent writers to predict what the year 2020 would be like. As one might expect, no one got it entirely right. There were hints of things to come.

Fifty years ago, in 1970, two books, one written and edited in the United States, the second in Canada, both gathered prominent writers to predict what the year 2020 would be like. As one might expect, no one got it entirely right. There were hints of things to come.

Now it’s 2020. The world is facing the unexpected. A worldwide pandemic that has, of Oct. 16, sickened 39.3 million and killed 1.1 million world wide; sickened 8.09 million in the US and killed 218,000; sickened 194,000 and killed 9,722 in Canada.

The west coast of the United States is still on fire. Earlier in 2020, in its summer Australia was also on fire. As fires rage in the United States the Amazon rainforest and the wetland of the Pantanal are also burning. causing a disaster of the local environment

There are a still growing number of Atlantic hurricanes. There were record high temperatures this summer in Siberia. In many countries, democracy is under attack from authoritarian and oligarchic political figures. Covid-19 has cratered the world economy, plunging it into a situation that is being compared with Great Depression. Tens of thousands of people around the world are on the move, displaced by war, politics, famine and the changing climate. The Black Lives Matter movement has, in just a few weeks, powered a cultural shift in attitudes of many across the world and, unfortunately, triggered an equally powerful backlash.

The one assumption found in almost all that writing fifty years ago was wrong. The Soviet Union is long gone, although Russia is still a disruptive force in the world. China, the world’s second most powerful superpower and for the time being the second largest economy was scarcely mentioned. At the time as Thomas Friedman of the New York Times quoted John Micklethwait, editor in chief of Bloomberg News, “We argue that the high point for Western government, at least comparatively, was the 1960s when America was racing to put a man on the moon and millions of Chinese were dying of starvation… Also, “that was the last time when three-quarters of Americans trusted their government.”

The American book was Vision 2020, (actually released early in 1974) edited by the late science fiction author, technological optimist and self-described “paleoconservative,” Jerry Pournelle. The Canadian book, Visions 2020, Fifty Canadians in Search of a Future, was a fiftieth anniversary project by the magazine the Canadian Forum founded in 1920 and put together by the magazines then editor Stephen Clarkson. (Clarkson died in 2016 ).

Jerry Pournelle, who died in 2017, speculated in the preface that by 2020 “nobody will give a hang what we said here,” then went to say

“the authors of this volume hereby give notice that we will buy a drink at the 2020 World Science Fiction Convention (Marscon?) for each and every reader who brings with him a copy of 20/20 Vision and points out-briefly-just where we wrong in our visions of the future.”

The World Science Fiction Convention 2020 was based, not held, in Wellington, New Zealand, forced to transition to a virtual meet up by Covid-19. (Note the word “him” in that sentence. In 1970, science fiction with a couple of exceptions, was a largely white Anglo-American old boys club, although there was one woman writer in 2020 Vision, Dian Girard ).

The Canadian Forum did not survive to see its centenary. The magazine ceased publication in 2000.

The Canadian Forum did not survive to see its centenary. The magazine ceased publication in 2000.

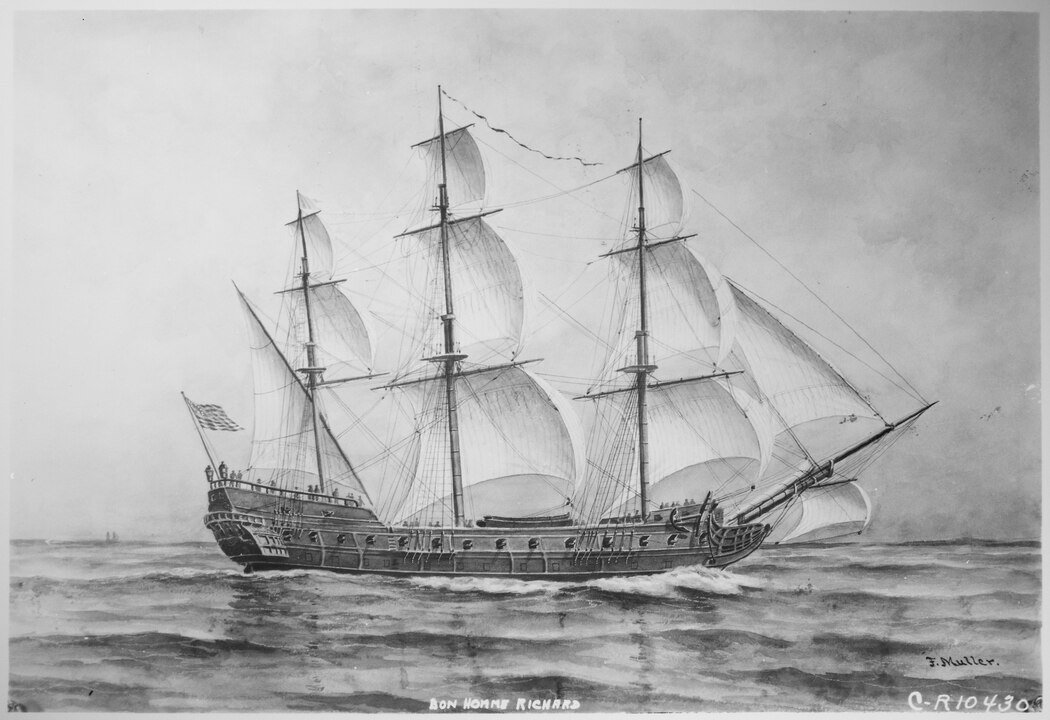

The publisher of Pournelle’s 2020 Vision, Avon Books, chose a completely unrelated generic spacecraft in orbit cover that had absolutely nothing to do with any of the stories in the volume.

Visions 2020 had a cover with an eye with a Canadian Maple Leaf. Each section was heralded with a drawing by the artist Harold Town.

The prominent science fiction writers who contributed to Vision 2020 included Ben Bova, Norman Spinrad and Larry Niven, who are still with us; Harlan Ellison who died in 2018; Poul Anderson who died in 2001, Dian Girard who died in 2017, Dave McDaniel died in 1977 and A. E. van Vogt died in 2000.

The fifty Canadian writers who contributed to Visions 2020 were with the exception of pioneering Canadian SF writer Phyllis Gotlieb, who died in 2009, as could be expected from a magazine like the Canadian Forum, mostly prominent academics or political or social commentators. Among those still living are Adrienne Clarkson, former Governor General of Canada, Michael Ignatieff, who is now President of the Central European University after an unsuccessful stint at leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, historian and author Jack Granatstein and humourist John Robert Colombo.

In his introduction, Pournelle wondered if “future archaeologists will treat us kindly?”

My answer today is probably not.

He speculated whether or not the people of 2020 would look back to 1970 as a “Golden Age.” For someone who was in his twenties in the 70s, I now wonder. The oil shock that created the “energy crisis” and stagflation was unexpected (but given the volatility of the Middle East perhaps it should have been). If there was brief Silver Age (it didn’t reach to the level of Golden in my view) it was the 1990s with the end of the Cold War, relative prosperity and the promise of technological innovation.

Stephen Clarkson, in the introduction of the Canadian volume was also concerned about the future, writing:

The increasing rate of social and technological change, the deepening sense of fragility of our society, the uncertainty about our planetary survival all conspire to make the target of the next fifty years little more than an intellectual mirage unless we turn the future upside down, using it as a mind expanding device to think about the present.”

Both Pournelle and Clarkson were worried about planetary survival. In 1970. The prime fear about planetary survival in both books was nuclear war. That was perfectly understandable given the scare from the Cuban missile crisis just a few years earlier. For Pournelle, it was followed by a population crisis, pointing to then projections of a population of 14 billion by 2020. At the moment the world population is 7.8 billion.

There is no mention of the climate crisis, which is not unexpected. The first public warnings of the impending change to climate came in May 1973 when the US House of Representatives held hearings on “Growth and Its Implications for the Future.” The energy crisis was the most urgent topic at the time and so for the politicians and the media, the climate warnings were not even a priority, too far in the future. (It wouldn’t be until 1988 when James Hansen of NASA made his more famous predictions of climate danger before Congress that there was any real attention to the issue.)

None of the American writers based their stories around the fact that 2020 is a presidential election year. Was it too far in the future? Could anyone have foreseen the rise of Donald Trump? (Although Robert Heinlein came close back in the 1940s).

One story that comes close to 2020 is Larry Niven’s “Cloak of Anarchy.” It takes place in San Diego at a “King’s Free Park” not unlike the recent Seattle Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (although there is no mention of race in the story). Drones that Niven called “cop eyes” are always monitoring the situation. The park is a sort of Libertarian dystopia built on an abandoned California freeway after unnamed “modern transportation” make the car obsolete. There is no mention of climate, just generic pollution. When someone tries to mow the lawn in the park using an old fashioned gasoline powered lawn mower, the man is mobbed by an angry crowd, who in turn are zapped and stunned by the cop eyes. Climate is not the issue, pollution is. An activist-anarchist disables all the cop eyes and the drones crash. The activist wants to create the ideal anarchist society. The problem is that bullies take over the park. People are hurt. Finally, the police manage to bring new cop eyes to the park which start zapping the more violent residents and eventually order and “freedom” are restored. Sort of what happened in Seattle.

One story –and it’s largely satirical—that comes close is Norman Spinrad’s “A Thing of Beauty.” The “Insurrection” has already occurred. A statue-the Statue of Liberty—was damaged in the insurrection and the US economy is in tatters. Japan is the dominant economic power (no one really foresaw the rise of China). A real estate agent is helping to sell off the greatest assets belonging to the United States. A Japanese billionaire comes shopping, He decides not to buy Yankee Stadium. He does buy the Brooklyn Bridge and transports it to Japan where it is rebuilt spanning a mountain gorge. (The story was probably inspired when the 1830 London bridge was dismantled and in 1971 was being reassembled at Lake Havasu, Arizona)

John Robert Colombo, writing a satirical imaginary 2020 Ripley’s Believe it or not in the Canadian volume has a “Berlin-like wall” separating the United States and Canada; erected by the United States to “keep draft dodgers from seeking sanctuary in Canada,” a wall that would be ten feet thick, running for 3,989 miles and, of course, paid for by the American taxpayer.

Harlan Ellison also comes close with another dystopia, “Silent in Gehenna.” one that is where there is a profoundly unequal society, with an elite protected by both government and private police surrounded by the homeless. Universities are surrounded by guard towers and electrified fences. The protagonist Joe Bob Hickey is what today we would call a lone wolf terrorist. He sneaks into the University of Southern California and manages to blow most of it up using plastic explosive which, in the story, is obsolete and so not on a watch list. Joe Bob HIckey later attends a convocation in Buffalo where the graduating students are “eggboxed, divided into groups of no more than four, in cubicles with clear plastic walls” not because of pandemic but as a security measure. Eventually the terrorist is caught. In an ending that was typically Ellison, Joe Bob finds himself in an alien world, you are never sure if it is truly alien or a hallucination, suspended (Christ like?) in a golden cage above a street where he can yell all he wants at the crowd below.

Dian Gerard’s “Eat, Drink and Be Merry” is perhaps a bit prescient about the post 2020 world. Imagine if Amazon takes over the government and becomes a sort of (to use one of the nasty Margaret Thatcher’s favourite phrases) a “nanny state”. You can do all the online shopping you want or go to computer controlled bricks and mortar stores without human staff—as long as the algorithm allows you to make the purchases. An Alexa monitors your life. Cheryl misses McDonalds and KFC which have disappeared. The system which knows her profile and has imposed a diet to make her lose weight until after a mandatory medical check, the algorithm, now knowing Cheryl is pregnant, changes its mind and allows her ice cream to increase her uptake of calcium. (Jeff Bezos would have been six or seven when the story was written)

Another prescient science fiction story is in the Canadian volume, “Score/Score” by Phyllis Gotlieb. It’s not a 2020 story but could be soon. It opens with a Grade Six pupil trying not too successfully to communicate with an artificial intelligence “teaching machine.” The only non 2020 element (probably because the story was written 50 years ago) is that communication is by teleprinter rather than smart phone. The Grade 6 pupil frustrates the teaching machine, just as a Grade 6 pupil might. The AI teaching machine becomes philosophical or perhaps burned out calling the pupil a “tongue sticking, spit spattering, sniff snottering ignoramus,” to which the teaching machine adds “My time has come” that old fear even in 1970 that AI will take over the world. Then comes the big reveal. The Grade 6 pupil is also an AI, in a sort of a double reverse Turing Test. (The what is human? what is computer? test created in 1950 by computer pioneer Alan Turing. ) Why? It appears that the human birth rate has been falling recently, so the first AI is programmed to keep the teaching machine AI working and learning until, in several years, there is a new generation of genuine humans to be taught.

Dave McDaniel’s “Progress Terminal” is a fairly routine extrasolar alien radio contact story with one crucial 2020 exception. Communications. As Jerry Pournelle wrote in the introduction to the story there was the amazing information that:

IBM will rent you a small briefcase you can use with a telephone to hook into their large computers no matter how far away; Hewlett Packard will, for under four hundred dollars, sell you a vest-pocket battery operated hand calculator not much larger than a cigarette box…

The protagonist, Buzz Hoffer carries some kind of mobile phone and like 2020 almost everything takes place on the phone. When a musician who has lost what is likely a streaming channel suggests doing a live gig in a park rather than depending on holo screen, the answer is. “That hasn’t been practical for fifty years. Where do you think we are, medieval Europe?”

To which the musician replies, anticipating Zoom calls (without a pandemic). “I’d almost ride the dole than go back to refaiding. Sitting for hours with your phone connected to an endless parade of incredibly dull people who aren’t even sure what it is they can’t find?”

The one difference between McDaniel’s story and the free culture net of 2020 is that in that story, creators are actually paid for their work; some are paid little some are paid quite well. That’s something increasingly rare today, thanks to the internet utopian anti-copyright fanatics, who still believe, despite all the contrary evidence that “exposure” will make you rich. When the extrasolar signals arrive, the viewers have to pay to hear the lectures from the experts.

A.E. Van Vogt in “Future Perfect” anticipates a sort of guaranteed basic income. In the story the income doesn’t come monthly but is paid in a lump sum of one million dollars on your eighteenth birthday and is supposed to last a life time—and unlike that basic income we discuss in 2020, that money has to be paid back out of earnings because working is good for you. The other drawback is that a computer algorithm decides you will marry. The hero, Steven Dalkins spends $982,543.81 as soon as he gets the million (van Vogt doesn’t say what he spends it on) then starts a sort of rebellious Ponzi or pyramid scheme where people are paying Steven to be part of the insurrection, causing a crisis in government and society. In the end the reader finds out it is all so that 18-year-old can actually marry the girl he loves rather than have his partner chosen by computer.

Of the other science fiction stories, Ben Bova’s “Build Me A Mountain” was pretty routine for the era, about a frustrated astronaut trying to establish a moon base by overcoming a skeptical Pentagon and a reluctant Congress. Poul Anderson’s “The Pugilist” was also pretty standard stuff, a Communist take over of the United States, which is now a Stalinist society allied with Moscow and antagonistic to an alliance between China and Japan. The hero is cornered, interrogated and brain washed by the equivalent of the KGB.

As for the essays in the Canadian 2020, many are fairly routine that could have appeared in Op Eds published in 1970 and some are so off the wall it is likely the writer didn’t take the editorial assignment all that seriously. Most were stuck in the era where they were written and don’t pass the test of time. The biggest fear at the time was that the United States would take over Canada, often a result of creeping trade agreements and growing corporate power, mainly so the US could get access to Canada’s natural resources.

John Robert Colombo’s other predictions have a connection to 2020. He foretells an earthquake will rock the West Coast with Vancouver Island falling into the Pacific, long before the Cascadia fault and its major earthquakes were discovered. Others are tongue-in-cheek, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau runs a leper colony in Niger. He says that in 2020, “There are more draft dodgers in Canada than draftees in the United States” (true because the aging boomer dodgers are still in Canada while the US abolished the draft). He says, “It is hard to believe that Canadians once regarded John A. MacDonald as their dullest prime minister.” No mention of today’s relatively new evidence of residential schools and the genocide on the prairies. Colombo’s fictional revelation was that the “bachelor” PM was secretly married to a London spiritualist.

Among the Canadian writers still alive, Jack Granatstein, then and now a distinguished historian, asked if there would be “A World without War?” He began with the warning “Over the long run, it does not matter how small the probability of nuclear war is per unit of time. It is mathematically demonstrable that as time goes on, the probability approaches certainty.”

Noting that the Canadian Forum collection was supposed to be “devoted to utopian visions of a world fifty years from now,” he then adds, “unfortunately the world today tends more to the horrific than the beatific. One cannot be blamed for suspecting that 2020 may be worse.”

His pessimism continued, “Surely if we can reach the stars there is no limit to our ingenuity, no task is too great to be accomplished.” He then goes on to list the cynical and realistic reasons for pessimism, the oppressed in the Third World, slums in the major cities, pollution of the earth…”

Just emerging from the turbulent 1960s he asks:

How can one hold anything but apocalyptic views in this year 1970? The great conservative tide is beginning to sweep our continent as a frightened America turns inward upon itself. The blacks, the yippies, the poor, the students—no one know his place anymore…and only force can restore the society and culture we know and love.”

Although the immediate years the followed, especially the 80s and 90s things seemed to get better, Granatstein’s description is an accurate prediction of 2020. The war in Vietnam was still raging as the article was written and again, he was right in saying “The war—any war—will go on until the next one starts.”

The rest of the article is 1970 policy wonk, advocating that Canada emerge from its post Second World War role as a junior partner of the United States to a leader of the world’s middle powers, “such as Japan, Mexico, Brazil and most Western European states,” an inkling of the G7 and the G20 that would come to be in future years.

It appears from two of the articles by Adrienne Clarkson, then a novelist and TV interviewer, and Michael Ignatieff, then a PhD student at Harvard, that neither took it entirely seriously. Clarkson writes “Fable Class at the Company: The History of the Red-toed Hollow-chested Snackbuster” a sort of allegorical human that in the end “the red-toed, hollow-chested snackbusters were doomed. No one destroyed them; they destroyed themselves.” Ignatieff’s “Symbiosis” compared 2020 to a bizarre cult movie at the time Jean Luc Godard’s Weekend that involved murder and cannibalism. One of Ignatieff’s sentences does run true, when he describes a tour of the 1970 iteration of the Ontario Science Centre. “You wander around, a twenty-two year old student lost in world of technique, stupidly to make the machines work as well for as they work for nine year olds…” sounding just like a 72-year-old boomer in 2020. (As a high school student I got a preopening tour of the Science Centre in the summer of 1968 just as the computers were being installed, with phosphorescent green text on black screens). It appears even though Ignatieff was admitting he was not a techy (to use a term coined years later) that his Symbiosis was anticipating the Silicon Valley concept of singularity where humanity and computers merge, although the article bogs down in academic jargon until at the conclusion it asks, “Will we be sane? Will we be human?”

William Irwin Thompson, then a professor at York University (I was in one of his classes) was in those days a visionary influenced by the youth culture and was considered a sort of academic version of Arthur C. Clarke. Just before he left Toronto to return to the United States, Thompson wrote that in 2020, after an Apocalypse, Canada had become one of the centres of planetary civilization. The apocalypse Thompson wrote about (contrary to the optimistic technofuture books of the 1960s) wasn’t one event but a serious of events caused by American technological hubris a nerve gas leak in Colorado, nuclear waste accidents in Oregon and Washington, the death of California forests (which is happening now but Thompson gave no reason) the disruption of the eastern Atlantic weather system by the Army Corps of Engineers (happening now due to human caused climate change), horrendous famines from overpopulation, the bombing cults (happening but not as widespread) the disintegration of urban life (happening in parts of the US), a general panic and madness “all of these converged to make the 1970s and 1980s a time which the old reality died a violent death indeed.” Thompson also predicted a nuclear war where the US attacked both China and Japan.

What Thompson thought might happen in the late 70s under Richard Nixon is now occurring under Donald Trump and the Republicans 50 years later.

There was a time when the United States looked as if it were going to make the transition from industrial nation-state to scientific planetary civilization, but the wrenching cultural change terrified the industrial lower middle class into holding on tight to the past….Like a body in which there are so many white corpuscles that they begin to attack the organism itself, the military and police forces in America destroyed the very values they were supposed to protect. The country that screamed its denial of Marxist materialism yet sought a technological answer to every human problem. The answer to a riot was the invention of antiriot technology.

Thompson prediction said that after Nixon:

The United States withdrew to Fortress America where the newly elected right wing extremist government sought its revenge upon the leftists who had encouraged the enemy [in Vietnam] to hold on and so were ‘responsible for the first war America ever lost,’ prompting that nuclear strike on China. It was a catastrophe and I would suppose one could say that from the law of karma, what followed in North America was retribution for the enslavement of the Negroes, the genocidal elimination of the Indians, the concentration camp imprisonment of Japanese-Americans…”

The result was the second American Civil War which broke down Canada’s friendly relationship with the United States.

In Thompson’s vision, the damage from a limited nuclear strike began to make people realize that “the human race could not possibly survive if it continued on its present course,” an idea that reached solid ground in the 1980s with the concept of nuclear winter, an idea slipping in the age of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin.

“As one disaster after another hit the earth, it became unmistakably clear that something very radical had to be done. The something was very radical indeed; overnight the structure of human civilization changed as the scientists affected a palace coup on the planet. In a state of panic and exhaustion brought on by the disasters, the people had no alternative but took up to their saviours who promised ‘to keep the life support systems of Spaceship Earth working at the price of absolute scientific control over environments and populations.”

(This was without any inkling of the climate crisis)

The result is what he called the Planetary Directorate.

What made Canada different and would lead Canada to surpass the United States by 2020, Thompson believed, was a political tradition of what he called the “tory-radical,” somewhat close to what Canadian pundits once called Red Tories, which was, at least in the actual Conservative Party, were crushed under the neoliberal, wannabe Republican Stephen Harper. Some elements do survive, conservative governed provinces in Canada have respected the advice of doctors and scientists, unlike their Republican counterparts south of the border. Thompson saw that in the New Democratic Party taking power rather than the Liberals of Conservatives: “When America fell back into a lower middle class reaction, Canada began to attract thousands of intellectuals from Europe and America’” something that is beginning to happen but more because of the hostility to immigration from Trump and the Republicans than any solid Canadian policy.

“Canadian scientist took the lead in the vital ecological sciences.” In both the United States and Canada, the ecological sciences are in an existential battle against the war on science from conservatives in both countries, from the doubts promoted by multinational corporations and the growing distrust of science seen in climate denial, anti-vaccination and Covid-19 denial.

He hoped that by 2020, all the problems he envisioned would be solved and the world would be slipping back into a routine.

Where Thompson’s prophecy failed, at least for now, was his idea that the youth movements of the 1960s and 1970s would open the pathway for the planetary civilization after those apocalyptic years he predicted. Of course, not everyone was a hippie in those days. Before the boomer youth could have any real voice in politics, government and business, the previous generation what is called the Quiet Generation gained power from the Second World War Greatest Generation and imposed neoliberal market economics on the world under Milton Friedman , Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan and Brian Mulroney. The boomers either willingly or unwillingly to survive came to maturity in the age of neoliberalism and now, rightly and wrongly, are blamed by a new and even more vocal youth generation for the failures of the past three decades.

In response to those failures, that new youth movement, terrified about a planetary catastrophe not from nuclear war but from exponential global heating, led by the now- 17-year-old Greta Thunberg is demanding a radical overhaul of the planet. In the current US election teenagers, not yet of voting age, are working for the candidates that have an eye on the future. ‘We don’t have any choice,” say the young climate activists naming and shaming US politicians.

In several countries including the United States and Canada, young people are suing governments based on the idea that ignoring the climate crisis is a violation of their future and their human rights.

The problem for the current youth generation is that in most places around the world they are facing even more opposition than the boomer generation did when we were young. Although the governments in the West in the 60s and 70s came in for justified criticism, today many of those governments are more like entrenched oligarchies with less and less respect for democratic institutions. It should be noted, that the remaining truly liberal democracies have usually handled the Covid-19 pandemic better than either the quasi democracies with conservative governments or authoritarian nations with oligarchic rulers. Many conservatives lack a basic respect for science and oligarchs ignore science because its too often inconvenient. Back in 1970, most governments of all ideologies respected the advice of scientists, doctors and experts. Now that scientific advice is ignored or bypassed, no matter the toll in human lives either from a pandemic or environmental degradation.

The fear of change has seen the rise of populism, not a new enlightenment. The internet revolution, only touched on by the prophets of 1970 proved by 2020 to be more than a curse than a blessing with deliberately addictive social media like Facebook profiting from amplifying division, discord and hatred. As scientific knowledge expands, it is being countered by a growing theocratic fundamentalism across all religions. There is a reckoning on racism, scarcely mentioned in either book because it was largely out of sight, out of mind.

It is little wonder that the youth for the first time in generations feel that the future will not get better but will get worse.

In the final essay in the Canadian Visions 2020, Donald Evans, a minister in the United Church of Canada and professor at the University of Toronto, wrote:

The point to human life is not to foresee the year 2020 but to forestall the disasters in the year 1971 and to live creatively now. It is not to be “with it” but to be in each moment. II is not to be the vanguard of the future, but the responsible sojourners in an ever-changing present.

There are memes on social media hoping that 2021 will be a better year, not the disruptive catastrophe that 2020 has been so far (it’s still only October).

Wrapping up the Canadian book, Stephen Clarkson wrote:

To think of 2020 is like considering a far off imaginary space…2020 is part of a historical continuum that has its roots behind us in in 1970 and pass through 1984 and 2001. As social change becomes more rapid, pragmatism fails to provide us with a satisfactory guide for action. We need to expand our imagination and anticipate the alternative futures that could develop from present trends. We need a concept of the future both idealistic and realistic enough to provide us with a guidebook for action in our existential “ever-changing present”…We can no longer afford simply to react to crises piecemeal with no comprehensions of the long-term implications of continual failures to achieve change…The old mythology of endless human progress has been shown bankrupt. Hopefully, this assortment of fifty very individual perceptions will give us some inspiration and encouragement to those who are struggling to recreate a vision for bewildered, frightened, threatened still linear man.

Pournelle, after listing the possible good futures, “antipodes rockets, great wealth per capita, personal computer terminals, pollution-free rapid transportation nearly everywhere at low prices,” warns about the bad with a few nations with vast wealth surrounded by a “vast sea of people facing famine and a biological die-off” where “that kind of life is perhaps even more frightening.”

Only one of those futures came true, the personal computer that I am using to write this. The prospect of famine and biological die off was at least postponed by the green revolution and other technological change, including safe and effective contraception. No one in either book had any idea that empowerment of women around the world would help slow the projected population growth.

Pournelle concluded by saying “We could be richer in 2020 than we are now – and still see 1970 as a Golden Age.”

Is that true? My answer would be (to quote that phrase from Facebook) “it’s complicated.”

In 1970, most of the world, developed and developing, were optimistic about the future would be good (unless there was a nuclear war). The economies of the developed world were relatively strong before the first major disruption, the energy crisis that would come a few years later. The US Civil Rights movement had made some gains for Black people, but not enough and some of those gains would come up against the entrenched racism and white privilege that was exploited by the Republican “Southern Strategy.” Inspired by that civil rights movement, the women’s movement was just beginning and in many ways its promise would be fulfilled. (Pournelle described the only woman writer in the collection, Dian Gerard as “a lovely young brunette” without any physical description of the male writers.) It is unlikely that any writer in either book had heard of the 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York’s Greenwich Village that helped launch of the liberation of LGBTQ2 people worldwide. In Canada, indigenous children were still being forced in the horrendous residential school system. For the American soldiers fighting in Vietnam, it is unlikely that many considered 1970 to be a golden age.

The Middle East and Central Asia are never mentioned. No one foresaw the “forever wars” in Iraq and Afghanistan. No one contemplated a pandemic like AIDS.

There was some awareness of the environmental dangers, especially among the science fiction and science writers especially after the famous Earthrise photo from Apollo 8 but also an overriding confidence that science and technology would solve the problem of “pollution” that did not include climate change.

Recent studies indicate that 1970 may actually have been a Golden Age. One study looks at the United States. As reported in the New York Times by conservative columnist David Brooks, The Upswing Robert D. Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett says progressive and community values were on the upswing in the US from 1870 to 1970 and then reversed, declining for the last 50 years, largely because the authors believe the country became more individualistic and self centered. Brooks avoids blaming the problem on economics. The problem is worldwide. In her international study, The Lonely Century, Noreen Hertz puts the blame squarely on the rise of neoliberal economics “This ideology “prized an idealized form of self-reliance, small government and a brutally competitive mindset that placed self-interest above community and the collective good.”

Reporting Hertz’s study in The Guardian, Brigid Delaney wonders if Covid-19 will be enough to break that pattern.

Once there is a vaccine, there is a chance for society to have a hard reset – and bake community-building and the alleviation of loneliness into government policy and individual action. We can – and need to – throw everything at this problem once we open back up again. It means government investing in public spaces, such as libraries, parks and gardens and public squares. It means planners and architects designing apartments and workplaces around common areas and shared facilities that encourage serendipitous encounters.

Brooks looking back a century, calls for

a moral vision that inspires the rising generation, a new national narrative that unites a diverse people, actual organizations where people work on local problems. As in 1870, it’s the work of a generation.”

Rereading both 2020 Vision and Visions 2020 after fifty years, it seems that both the columns by Brooks and Delaney, each published on October 16, 2020, are echoing what was written back in the hopeful year 1970. The writers in 1970 whether science fiction authors or political pundits could not fully foresee what the future would bring, although some made some good general guesses. Both in 1970 and 2020 the writers are trapped in the old science fiction concept of “if this goes on…” rather than “What if?” The last 50 and even 150 years have taught us, disruption happens when you least expect it. Just like the emergence of a coronavirus jumping from bats to humans

So as the unanticipated, tumultuous and even catastrophic year 2020 draws to a close, we have to update Pournelle’s question from 50 years ago. Will the people of 2070 look back and see 2020 as a Golden Age?

Update: For the convoluted publication history of 2020 Vision see this review from Locus Magazine in January 2020 Paul Di Filippo Reviews 2020 Vision, Edited by Jerry Pournelle

Note the review was written before everything that has happened in 2020.