It was “a dark and stormy night” in 1813

A dark and stormy night 1813 edition

(I don’t usually full post excerpts from my work in progress, I often put far too much into first drafts and then have to drastically cut.

This episode of “a dark and stormy night” I discovered is too good to pass up. I am working on stories about my fourth great grandfather William Pennell, who was what today would be called a spy under diplomatic cover as British Consul in Bahia, Brazil, monitoring the South Atlantic slave trade. That meant he often had to liaise with Royal Navy captains, including Sir George Ralph Collier who was commodore of the West Africa Squadron, tasked with supressing that slave trade.)

This episode of “a dark and stormy night” I discovered is too good to pass up. I am working on stories about my fourth great grandfather William Pennell, who was what today would be called a spy under diplomatic cover as British Consul in Bahia, Brazil, monitoring the South Atlantic slave trade. That meant he often had to liaise with Royal Navy captains, including Sir George Ralph Collier who was commodore of the West Africa Squadron, tasked with supressing that slave trade.)

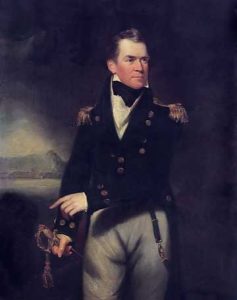

Prior to that in the Napoleonic Peninsular War, Collier commanded a small squadron of ships providing operational support to the then Marquis of Wellesley (later Duke of Wellington) . Collier was in over command during on operation that took place one dark and stormy night in 1813.

On July 12, 1965, Snoopy, as penned by Charles M. Schulz, dragged a portable typewriter to his dog house and began to type a novel starting with “It was a dark and stormy night.

I had just turned 15 at the time and just received an Olivetti portable typewriter for my birthday. I am sure every kid who wanted to be a writer was up there with Snoopy, the typewriter and the doghouse when the Peanuts strip arrived in the newspapers (in the good old days when there were newspapers in every home) and “it was a dark and stormy night” became ubiquitous.

The best known use of “it’s a dark and stormy” night comes from the opening line Edward Bulwer Lytton’s 1839 novel Paul Clifford.

As Wikipedia says that line is considered an archetype of “purple prose.”

It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents—except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

Recent research has shown that American author Washington Irving used the phrase in his

1809 satirical book A History of New York. (It wasn’t in the opening line)

“It was a dark and stormy night when the good Antony arrived at the creek (sagely denominated Haerlem river) which separates the island of Manna-hata from the mainland.”

Two years later, in 1832, Edgar Allan Poe used it in “The Bargain Lost,” like this:

It was a dark and stormy night. The rain fell in cataracts; and drowsy citizens started, from dreams of the deluge, to gaze upon the boisterous sea, which foamed and bellowed for admittance into the proud towers and marble palaces.

Unlike Snoopy, Bulwer-Lytton, Irving and Poe, Sir George Ralph Collier was a naval officer, writing an official formal after action report that would appear in the London Gazette on November 9, 1813, beating Bulwer Lytton by seventeen years.

He described the action between the Royal Navy schooner HMS Telegraph and the French corvette Filibustier.

The Filibustier had been waiting an opportunity to seal out of St. Jean du Luz for some months past; the near approach of the Marquis of Wellesley army made it absolutely necessary, and a dark and stormy night1 determined her commander to risk the attempt.”

In the summer of 1813, Arthur Wellesely, later the Duke of Wellington was attacking the Napoleon’s French forces and their allies along the north coast of Spain attempting to take the cities along the coast.

To simplify a complicated military situation for this blog, Collier’s small squadron was tasked with supporting the British forces with offshore support for the army and the Spanish guerillas and to help capture the strategic ports along the Bay of Biscay.

It was also the time of the war of 1812. Early in 1813, the Royal Navy captured an American privateer called the Vengeance and took the ship into the navy as HMS Telegraph. One of the swashbuckling young captains of the age, Timothy Scriven took command of the Telegraph in June 1813.

It was assigned to the Channel Fleet and operated mostly against American vessels.

On August 12, 1813, Telegraph chased for 44 hours and then captured the American schooner Ellen & Emelaine off Santander, Spain. On September 12, Telegraph captured four French vessels trying to reach Bordeaux. On September 22, Telegraph escorted a convoy from Plymouth to San Sebastian, bringing navy dispatches to Collier. Telegraph then joined Collier’s squadron. The British had recently captured San Sebastian after a siege and were using It as a base.

Wellesley meanwhile was preparing to cross the border and invade France.

The French still held the town of Santoña in Spain. Its garrison was holding out against a British siege. Capturing or neutralizing Santoña was crucial to protect Wellesley’s rear.

Across the Spanish border with France, the French held the fishing village of St. Jean du Luz, where the Filibustier and some smaller warships were based.

Watching St. Jean du Luz were HMS Telegraph, HMS Constant and HMS Challenger.

On October 13, Filibustier sailed from St. Jean du Luz, attempting to reach the nearby besieged garrison at Santoña. The escape attempt was, as Collier reported, “the approach of the Marquis of Wellesely’s army made it absolutely necessary, and a dark and stormy night1 determined her commander to risk the attempt.”

The Fillibustier was “carrying on board treasure, arms, ammunition and salt provisions and from her large compliment of men, probably some officers and soldiers for that garrison.”

The winds, however, carried the Fillibustier away from Spain toward Bayonne.

Before Filibustier could reach Bayonne it became becalmed at the mouth of the river Adour.

As night fell and the storm blew up again Telegraph spotted Filibustier and engaged, joined by Challenger and Constant.

Telegraph exchanged fire with the Filibustier for about three quarters of an hour. Either from the British cannons or perhaps deliberately set, Filibustier was on fire. The crew then abandoned the ship. Scriven sent his ship’s boats in an attempt to save the Filibustier and put out the fire.

That fire was so fierce, however, that the Telegraph’s boat crew had to abandon the ship after seizing the ship’s papers. The Filibustier then blew up. Lloyd’s List reported that there were 30 French wounded still on board, while Scriven reported “I have no means of ascertaining the enemy’s loss in killed and wounded, it must have been considerable, but I have the pleasure to state that the Telegraph did not lose a man.”

Collier also reported that the Filibustier was covered by the shore batteries at the mouth the Ardour and the encounter was “witnessed by some thousands of both armies.”

One wonders what other literary gems may lurk unnoticed in military dispatches

PS, Every year since 1982, writers have entered the

the Bulwer Lytton Fiction Contest that “has challenged participants to write an atrocious opening sentence to the worst novel never written.”

.

.

The Gazette, https://www.thegazette.co.uk/. No. 16803 November 9, 1813, p 2205

Lloyd’s List. No. 48920 November 9, 1813