My own private London. A gay life in the first year of It’s a Sin.

Version 2.0 Updated October 2023

Long read

(Contains spoilers for It’s a Sin and may trigger some AIDS survivor readers. Names in quotation marks are pseudonyms. Many of the names from the 80s aren’t mentioned because I don’t remember. Other names are real, taken from my occasional diary or letters I wrote)

This is an update along with corrections and some restructuring of my original account posted online in May 2021. This different account is now the one that reflects the events of the past two years, a 2022 post Covid trip to London and so a return to Earl’s Court. In 2023, I found “Darren’s” name on the Vancouver AIDS Memorial at Sunset Beach. Mourning after more than 30 years brought a different perspective on the events which I have added in italics. The original post still exists on Medium.

LONDON

The year 1981 was one of the happiest, craziest and upsetting times of my life. London in 1981—and that’s where I was living for that happy year– is the setting for the opening of Russell T. Davies’ international hit television series, It’s a Sin, about a group of young friends, most of them LGBTQ2S, enjoying the freedom of life in London on the cusp of a darker days ahead when HIV/AIDS would strike.

On January 22 of this year, 2021, as I do most mornings, I was casually reading The Guardian online over breakfast. As I scrolled down the page I spotted the headline “It’s a Sin review – Russell T Davies Aids drama is a poignant masterpiece“ with the publicity photo of a good looking young man, unidentified in the cutline, enjoying the affection of a second. That handsome devil—and in the show he is a bit of a devil—is Ritchie played by Olly Alexander.

Lucy Mangan’s review began rather ho hum for me, referencing Davies’ earlier gay series, Queer as Folk with a side reference to Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City, noting that the new five part series on Channel 4 in the UK ( on Amazon Prime in Canada and HBO Max in the US) followed “the lives of three young gay men…as they commit themselves to the enjoyment of every freedom the city has to offer.”

The next paragraph was an unexpected punch in my gut.

But the group arrive in 1981, just as the first reports of a new disease are making their way across the Atlantic. The shadows are starting to gather by the end of the first episode, which is mostly devoted to establishing the characters and their relationships in full measure. It is Davies’s great gift to be able to create real, flawed, entirely credible bundles of humanity and make it clear, without even momentary preachiness, how much they have to lose.

I will turn 71 this year. I am, by a stroke of luck or fate, HIV negative. I lived through those dark, dangerous years of the 1980s and 1990s, saw far too many friends, as the audience sees in It’s A Sin, gorgeous young men, first feel strange symptoms, then fall ill, become disfigured by the sores of Kaposi’s sarcoma and/or become human skeletons, as their immune symptoms slowly collapsed. Many friends died slowly as the Human Immunodeficiency Virus decayed the body’s defense systems. One friend appeared fine and healthy on a Friday and was dead by Sunday afternoon. Other friends, acquaintances or guys I had brought home one time or another, disappeared until I was notified about a funeral planned in the next few days. Others simply vanished, like Ritchie’s sometime boyfriend and acting rival. “He went home,” their agent Carol Carter (played by Tracy Ann Oberman) tells Ritchie. To which I would add, slightly out of context, perhaps unfair to the actors, but appropriate “And then is heard no more.”

I binged It’s a Sin on a weekend.

By the end of watching It’s a Sin, on that Saturday night, I was drained, weeping and amazed. As I dropped off to sleep, the thought came to me that I had just lived in one of the Greek philosopher Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. As Wikipedia says Plutarch’s biographies are “also about the times in which they lived.” Or as Hamlet says, the purpose of a play is “to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature” In my case it’s like my story is one of those side mirrors, that show nature from a slightly different angle.

First a note. Even these days it is necessary to change names and disguise locations. As Davies told The Guardian “There are things I can’t say here. Men I dare not name.” As another friend, Erik Piepenburg, wrote in the New York Times, “Then there was Will, my first boyfriend… and he said he would kill me if I used his real name.”

Much of my life and my world of that year in London in 1981 paralleled It’s A Sin. With one difference. I loved living there and had planned to stay in London indefinitely. A job in Fleet Street changed my life and plans. As a result of my brief time in that Fleet Street office, I unexpectedly received a job offer from Toronto. I returned in late October of that year. My life back in Canada in the 1980s paralleled the years in the subsequent four episodes back in the UK. Now I ask myself what would have happened to me had I stayed in London? Today I wonder what happened to all people I met during that year. I fear that among my gay friends from London in 1981 they did not survive.

There are differences. I had just turned 30. I was a “gay generation” older than the main characters in It’s a Sin, who are all about eighteen or so in 1981. Davies was about the same age, 18, when he came out in Manchester. It’s a Sin does reflect the life of an 18-year-old Londoner in that year. One young man, “Darren,” my partner at the time, who accompanied me to London, was 21, so he was part of that generation.

I’m in Heaven

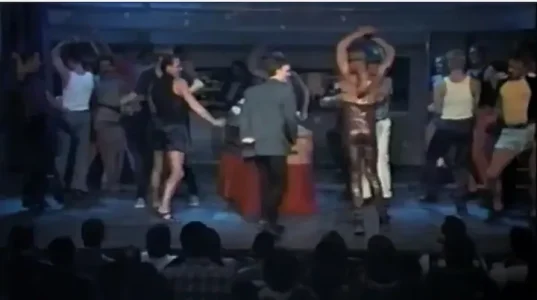

Some of the hottest scenes in It’s A Sin, take place in the London super dance club “Heaven,” called in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the “hippest place in Europe.”

One of the memorable moments in It’s a Sin is Ritchie’s monologue ( wonderfully played by Olly Alexander). The show cuts from gay scene to gay scene as Ritchie discounts every one of the then current theories about AIDS. The camera follows Ritchie as he says “It strikes, Homosexuals, Haitians and Hemophiliacs, like there’s a disease that’s targeted the letter H. Who’s it going to strike next, people in Harlepool and Hampshire and Hull? Do you see what all of these things have in common?” The camera then pans up as they silently pass the neon sign indicating they are entering Heaven. Great writing, directing and cinematography in that one last shot that takes a couple of seconds.

Later Ritchie’s face is so joyful as he dances crowded on all sides by the gorgeous men at Heaven.

When we got to London, “Darren” and I couldn’t wait until we could go to Heaven. It was about three weeks after we arrived, after I got the job in the “semi-gay pub” and had the day off and the extra cash for a night out. It’s a small world. We lined up. The man in front of us turned around. It was a man named Lynn that I knew from Toronto.

“Darren” and I went to Heaven about once a month or so, for the chance to let loose and dance.

In the summer of 1981, after “Darren’s” visa expired and he went back to Vancouver, while I stayed in London, I went to Heaven almost every weekend.

I kept an occasional diary that year. This entry could actually be right out of the script of It’s a Sin.

August 9, 1981

Went to Heaven. Packed with men—lots of men. Hot, sticky and wonderful. Met Randy the ex-Buddys bartender [Buddy’s was my favourite gay bar back in Toronto]. He had lived in New York and now London. Doesn’t miss Toronto….Walked around the floor, saw some real cuties. The atmosphere was hot, sweaty. Watched muscular go go dancers. Heavy, driving disco beat. Upstairs lots more men. Danced with a ruby haired man. Just interested in dancing but it was fun.

There are times on those hot summer nights that I did meet men at Heaven and go back to their flats. There is one I still remember. The most interesting guy I met was just before I was to leave to go back to Toronto. He was a gorgeous blond, a short guy, just my main type, probably in his early twenties, a newly minted accountant who had just moved to London from Manchester. He drove me back to his flat in Croydon. At one point on the way he pointed out that we were passing the infamous “bedlam” aka the Bethlem Royal Hospital mental hospital.

A couple of days later, I flew to Greece for ten days vacation and soon after that I was back in Toronto.

The memory of the cute accountant from Manchester has kept popping up in my mind once in a while over the years. After watching It’s A Sin, again comes the fearful thought. What happened to him? Is he still alive? Russell T. Davies was a gay teenager in Manchester which left me wondering could any of the characters in It’s A Sin be partially based on the good looking accountant who took me back to his flat a stone’s throw from Bedlam? He was younger than me, so the age is right.

What happened to the cute red head who asked me to dance? What happened to Randy who left Toronto for New York and then London at the critical moment at the start of the pandemic?

How many of the sweaty dancing men from those August nights in Heaven are still with us today? I was one of the lucky ones. There must be others.

As The Guardian’s Mangan wrote of It’s A Sin, it is a masterpiece. It’s a masterpiece because although I was 12 years older, it is also my life that you see on the screen. It’s A Sin is masterpiece that not only speaks to those of us who survived but now to many of the younger generations who don’t know what the hell it was really like.

The Crucible

On February 10, The Guardian brought together a “roundtable” of members of the community to discuss their personal reaction to It’s a Sin.

As part of the round table Marc Thompson, an HIV activist says,

I’ve spoken to a few people who just can’t watch it yet. They won’t watch it yet. It is too traumatising. We need to ensure that there is care and support for those of us who lived through it, those of us affected and the young people who carry the stigma on their backs. It’s a celebration and it’s joyful, but it’s triggering.”

I wasn’t going to avoid It’s A Sin. The fact that it began in 1981 in London meant I HAD to watch it.

As Charles Kaiser writes in the New York Times:

AIDS is the crucible living inside every gay writer old enough to remember it. It scratches away at our insides until we figure out how to wrestle with it. We must explain why we survived: mostly by dumb luck. And then do justice to the other half of our generation who did not — all those beautiful men who never made it past 40.

I HAD to watch It’s a Sin because 1981 in London made It’s a Sin deeply personal. Reading the review in The Guardian lit the fire under the crucible that melted the hardened metal that unlocked the memories and prompted me to write this.

I’ve gone to the plays, As Is, The Normal Heart, Angels in America, Jeffrey, watched the documentaries, read the “plague” books, the AIDS memoirs. All did speak to me about the AIDS years.

There is one problem.

As Omari Douglas, the Black man who plays Roscoe in the series, told The Guardian, ”All of my engagement with the epidemic and everything I had seen had been from an American perspective.” In her “Vulture” review for New York magazine.Kathryn Van Arendonk echoes the idea. “So many parts of the series are fun and funny and charming, and especially for American audiences, a story of the AIDS crisis based in London may bring a new facet to a story that’s often told as mostly about New York and San Francisco.”

Too often due to the dominance of the American media, the acknowledged talent of American artists and American exceptionalism, there’s an impression that HIV/AIDS happened almost exclusively in New York, Los Angeles or San Francisco. In one way that is a fair approach—at least in the beginning– because that was where the mysterious “gay cancer” first appeared. A handful of doctors were the first to struggle to make sense of what was happening. By 1982 and 1983, what later became known as AIDS was a worldwide crisis.

I am basing the title of this essay on a Canadian AIDS play, My Own Private Oshawa, written by my friend Jonathan Wilson, My Own Private Oshawa was a hit one man show in Ontario, neglected outside of Canada, and a later a television movie of the week for the CTV Network. My choice of title in part is a tribute to and mourning for our mutual friend, the main character “Gordon,” Wilson’s best buddy in My Own Private Oshawa. In many ways, “Gordon”, in real life, somewhat mirrored Ritchie in It’s a Sin. (I should note that My Own Private Oshawa is a poignant sometimes irreverent comedy not a drama) The deeper reason is that I now have a story that I must tell, a story I haven’t told my closest friends, of my life in my own private London in 1981.

The Back story

My father was English, my mother Scottish. That heritage meant I was eligible for a British passport that would allow me to work legally in London We came to Canada when I was about a year old and lived in northern British Columbia. I was an awkward geeky kid with thick coke bottle glasses. It would be decades later that I found that I had been born with a slight hip dysplasia that put my hips, knees and legs out of whack which is why I couldn’t run well with the other boys. I also had Attention Deficit Disorder that wasn’t diagnosed until I was 48—and what that did to my life and career if another story.

I was teased and bullied occasionally but it wasn’t that bad, it was survivable. I got along with most of the kids I grew up with (and a couple of years ago was invited to the 50th high school reunion even though I had left town the year before graduation).

When I was 16 our family moved to Toronto. I entered into high school hell. As I was writing this and I rewatched Jonathan Wilson’s My Own Private Oshawa, I thought I recognized the high school the film makers to substitute for that Oshawa high school hell for Jonathan and “Gordon.” The credit roll confirmed it, it was my old Toronto high school, that school that made my life hell for the first couple of years, Lawrence Park Collegiate that was used for location filming.

I was naïve to big city ways, the new kid in town, vulnerable feeling totally out of place. I hadn’t grown up with the other kids in school, they didn’t know me. I was gay although I didn’t know it at the time. I was an easy target.

It was the 60s, the closet years. I graduated from Lawrence Park in 1969, the year of the Stonewall Riots in New York, but didn’t find out about them until I came out almost a decade later.

It was not until I graduated with a BA from York University in Toronto and went on to take the “one year grad journalism” course at Carleton University in Ottawa that I began to realize that I was gay. There were gay dances at the University of Ottawa. As much as I wanted to do, I was too terrified to go.

It was two years later, about three quarters through my backpacking trip to Europe that I confirmed in my own my mind that I was gay. In the latter days of that trip, in Rome, Athens and the Greek islands, I met some very cute guys, who may have been straight, so I didn’t actually come out until I was back in Toronto.

I went to the Manatee, a popular and unlicensed dance club popular with what the guides of the era called YC “young collegiate”. Unlicensed meant you didn’t have to show ID to get in. Ages ranged from 16 to just under 30. I met a guy named Rick who was an occasional go go boy at the Manatee. He told me there was another Carleton grad in his Gay Youth Toronto support group. That was Jim Jefferson, already a reporter for The Globe and Mail, who had been the four year undergrad program while I was in the grad program. I had seen in him the halls but never actually met him in person until then. Rick and Jim brought me to a Gay Youth Toronto meeting, which eased my way into the community and the heady exploration of gay life in Toronto in 1977.

The late 70s and the first couple of years in the 80s, as portrayed in It’s a Sin, and in My Own Private Oshawa, were a paradise of freedom, adventure, sex and often love if you were young and gay.

There’s a fact in the gay community that is seldom mentioned. Rick was a guy who I had sex with just a couple of times. You meet a guy, you bond, you have sex only once of twice then you never have sex again, but the guy becomes a buddy, a friend, a friend for a few years, or if you’re lucky a lifelong friend. (I do have friends today like that who have survived)

Rick was such a man. In the 1980s, after I returned to Toronto, I met him now and again in Toronto’s Church Street Village. He had changed his look from go go boy to clone. .He joked with me once that he was “a fighter in the clone wars” (referring to what was called a “Castro Clone” short hair, moustache, lumberjack shirt, work boots).

After the mid-1980s I did not see him. In the early 2000s, I tried to find Rick with no luck. I knew that he was photographed in the late 70s by a prominent portrait photographer for a feature on gay Toronto. I contacted the photographer’s gallery. After a search, the gallery informed me that unfortunately the negatives had been lost over the decades. I recently talked to a mutual friend who told me he hadn’t heard from Rick since the early 1990s.

Apart from our lovers and ex-lovers, it is the friends like Rick we miss the most.

That summer on the Castro

In the winter of 1979, Rick moved to San Francisco, where he worked as an undocumented house boy for a gay couple, paid, of course, in cash.

In late May and early June 1979, I spent three weeks with Rick in San Francisco. I arrived just a few days after the “White Riots” protesting the acquittal of Dan White for the murder of Harvey Milk. The older gay neighborhood on Polk Street was still vibrant while the Castro was becoming the centre of gravity. There was a residential hotel for seniors just off Polk Street, in the Tenderloin, that also did a bit of side hustle underground business putting up visiting gay men in unoccupied rooms. That was where Rick had stayed when he first arrived and where I stayed for my vacation.

What word can describe those three weeks in San Francisco in the summer of 1979? That word has to be liberation but that doesn’t tell it all, liberation from everything that you had bottled up inside for 29 years. Even as Toronto’s gay village was starting to grow, there was still a restraint in what was left of old Protestant Toronto the Good. That restraint was long gone, at least in The Castro and Polk Street.

It wasn’t just the easy availability of sex, it was the conversations in the bars, bars, like the Midnight Sun, or the Elephant Walk that had been brutally raided by the San Francisco cops just a few days earlier.

It was the photographer on the Castro selling “souvenir postcards” of the police riot. I sent a postcard back to Jim Jefferson back in Toronto with the old cliché “Having a wonderful time. Wish you were here.” It was the giant milk billboard over Castro and Market with then trademark white milk moustache –but in this case the model was a hunky muscle boy in a yellow tank top.

It was the people you met, the friends of friends, the clothes you bought at All American Boy, h(which survived until 2008 ).

It was just being able to walk down the street being totally free, totally yourself, totally relaxed (while your eyes searched out cute men).

In one of those casual conversations, (if I remember correctly it was at the more relaxed Twin Peaks. ) I mentioned that I was also in town to attend the science fiction convention, Westercon ’79. “You’ve got to talk to Eric,” the guy told me. “He’s writing a history of gay science fiction. He’s just down the block here on the Castro.” (or something like that)

So that’s what I did. I buzzed the apartment and Eric Garber came down and we had coffee. His roommate at the time and prominent gay activist Cleve Jones (later the founder of the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt) described Eric in his book When We Rise, as “short, one of those strawberry blond types with blond hair and a reddish beard, He had a small belly and a wide smile and was one of the smartest and kindest people I have ever known.” Eric was just my type. All we did was discuss science fiction, exchange lists of books and talk about the future first on the Castro and later at Westercon. Eric’s work, with Lyn Paleo, was later published as Uranian Worlds.

So that’s what I did. I buzzed the apartment and Eric Garber came down and we had coffee. His roommate at the time and prominent gay activist Cleve Jones (later the founder of the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt) described Eric in his book When We Rise, as “short, one of those strawberry blond types with blond hair and a reddish beard, He had a small belly and a wide smile and was one of the smartest and kindest people I have ever known.” Eric was just my type. All we did was discuss science fiction, exchange lists of books and talk about the future first on the Castro and later at Westercon. Eric’s work, with Lyn Paleo, was later published as Uranian Worlds.

The others thing that was memorable about that Westercon 79 were the guys in the hallway of the hotel, several dressed in the uniforms from the original Battlestar Galactica, cruising each other.

UPDATE: Although everyone then called it Westercon 79 after the year, it is now often referred to as Westercon 32 as with the passage of the years, the numbers are geting up and the 2024 Westercon was Westercon 76.

One night, after not meeting anyone on the Castro, I walked into an almost empty bar on Polk Street for one last look around before going back to my hotel. A blond guy made eye contact with me as he was playing pool, so I stuck around, leaning against a railing as he finished the game and came over and said hello.

He was a little taller than me (I usually go for guys my height or shorter) but quite good looking. We had a drink. We went back to his place. We met up over my last couple of days in San Francisco before I was to fly back to Toronto. He was from a small town in Alabama. He was hearing impaired and required a hearing aid, which made his small town life, since he was perceived to be gay, even worse. He told me that soon as possible he and his best friend from high school, a lesbian, had fled to San Francisco.

I had his name, address and phone number in that kind of little spiral notebook that writers always carry to jot down ideas. (Today people do it on their phones)

We wrote to each other a couple of times.

Foolishly and perhaps because of my ADD, I never got around to transferring his address nor Eric’s nor the couple of other guys I had met in San Francisco to my address book. Somehow, I lost the notebook in my moves the following year from Toronto to Vancouver and Vancouver to London.

I have to wonder what happened to those guys I met in that hot summer; how much I regret losing that notebook because I have to presume that they’re gone.

A dozen years later in 1992. I met Eric at Gaylaxicon in Philadelphia. He recognized me immediately and gave me a big hug. We caught up on how much the science fiction world had evolved since we had last met. He died in 1995, another loss to our community.

I didn’t return to the Castro until 1993, when I was attending a tech conference in San Jose. Compared the summer joy, that year it was terribly depressing, partly because it was October and cold, wet and raining, with what appeared to be old men limping down the street and sparse crowds in the bars or cafes. A few years later the AIDS treatment cocktail became available, so my next visits to San Francisco in 2000 and 2002, both also in the summer, the Castro was once more alive.

Vancouver then London

In the months after the trip to San Francisco, I began to evaluate what I was doing. I wasn’t getting anywhere with my job at CBC News. I quit and moved to Vancouver. A job I had hoped for a job on one of Vancouver’s dailies fell through when Canada’s then big newspaper chains Southam and Thomson made a deal to exchange some papers and close others.

I met “Darren” at the most popular disco in Vancouver, The Gandy Dancer. He was a good looking young man with a mop of unruly curly hair. He told me he was an aspiring actor and that he had just returned from a trip to Los Angeles to check it out. In those heady days I had already met a lot of men in Vancouver, but despite the age difference of nine years, “Darren” and fell for each other.

“Darren” was a bit of a volatile character, but in retrospect, in some ways that appealed to the ADD in me. He was more stimulating than some of the other men I had met. About two and a half months later he moved in with me.

Times were tough. With that promised job gone, unemployment running out and some bare bones freelance work, and Darren working part time, what were we to do?

UPDATE: Despite our rather strained economic circumstances in 1980, we were still able to move in to and rent a nice new two bedroom condo in Vancouver’s fashionable and gay West End. That is clearly impossible to today after fifty years of economic mismanagment by both Conservative and Liberal governments and neoliberal economics that concentrated on building condos just for investors not people. In my trip to Vancouver in the fall of 2023, I met a server in a West End restaurant popular with the LGBTQ2S community. He is paying $2,000 a month for a small apartment on a server’s salaru, presumably minimum wage.

London beckoned. There’s an old tradition among Canadian journalists frustrated with their work at home. Move to London, get a job, on Fleet Street, with an American network, with a magazine or freelance and head for a hot spot to make your career. London did give me a new career in journalism for the next forty years—but not the way I expected.

“Darren” also wanted to go to London, to try to get into one of the city’s famous acting schools. We scraped together what money we had. It was just enough to fly to Toronto, take a bus to New York and fly standby from Kennedy Airport on a British Airways 747 to London Heathrow. We landed in the first week of December 1980, and checked into a bed and breakfast, on Courtfield Gardens in Earls Court.

The craziest Bed and Breakfast in London

We knew where we wanted to stay. Earl’s Court, then one of the centres of gay life in London. We had Let’s Go, the Harvard student guide to the UK. The first place we called had vacancies, so off we went on the long tube journey from Heathrow to Earl’s Court and found our way into one of the elegant garden squares and to a columned mid-Victorian building, a bed and breakfast I will call the “King Richard’s Court Hotel.”

In The Guardian, Russell Davies described the Pink Palace, home to the characters of It’s A Sin, the scene of much of the drama, this way through his eyes and that of his alter ego Ritchie.

“Jill … moved into a flat which she called the Pink Palace, and it felt like an endless party, the rooms filled with gay men and drag queens and show tunes.”

“King Richard’s Court Hotel” was my Pink Palace.

It wasn’t all that gay, certainly no drag queens (at least in costume) and parties were not allowed.

Through the months we lived at “King Richard’s Court,” I met the greatest assortment of crazy characters collected in one place that I have come across before or since.

There is a long history of British “B&B” theatre and movies, comedy, mystery (usually murder mystery) and “kitchen sink drama.” In my admittedly biased memory if the Richard’s Court wasn’t the craziest bed and breakfast in London in 1981, it was certainly in the top ten. I have always wanted to write a play or novel or something about that bed and breakfast but so far haven’t been able to find the write angle that would make it work.

To mention just a few of the people I met there:

The landlady was a tall, somewhat domineering woman with long blond hair, who we were told, had in her younger days, been an Olympic athlete who had defected to Britain from an eastern European Iron Curtain country. She ran a tight ship, along with her beefy British husband and her teenage daughter who was forever chasing the teenage male guests when her mother wasn’t watching. “Darren” started calling our landlady “Broomhilda.”

We were among the longer term residents. There were a couple of nurses working for Britain’s NHS, one Canadian, named Jill, the other an Australian, named Beth.

There was a dance student from Philadelphia, (straight as far as I remember) who sometimes popped pills and who claimed that his father, a member of IATSE, the stagehands’ union was connected to the Philly Mafia.

One young American who stayed for part of the winter had just graduated with a degree in Middle Eastern studies and was heading for that region. He later became, for a while, a photographer for one of the world’s major newswires.

There was a closeted low-level political appointee from the Reagan administration who rather presciently (given what is happening today) kept coming up with conspiracy theories that he tried to convince us were true, starting with the Kennedy assassination and getting wilder after that. He was a sad man who couldn’t be “out” in Washington, DC, so that was why he came to London and Earl’s Court.

There was a young married couple Steve and Jan from Washington State, who had just graduated as architects, committed to sustainable construction and even then, in 1981 (as I was) concerned about the growing threat of climate change.

There was one phone on each floor, connected to the same number as the hotel itself. In the middle of winter, every night for a week, there was one young woman who woke up in the middle of the night and entertained most of the house by calling her boyfriend collect somewhere back in the States and telling him at the top of her lungs how much she missed him.

Everyone would look at her at breakfast. She never figured out why.

“King Richards Court” had a television lounge. It was there that the guests, long term and temporary, would get together, British, Canadian, American, Australian. On April 12, 1981, “Broomhilda” allowed the room to stay open past the usual curfew so we could all watch the first launch of the space shuttle Columbia. One show that everyone quickly came to love, including the visiting Americans, was the famous and funny British political comedy Yes Minister on the BBC (Yes Minister still draws audiences 40 years later on You Tube and social media).

The TV was never on at breakfast. When we had been in London for about a week, on the morning of December 9, 1980, we didn’t know that John Lennon had been assassinated in New York the previous afternoon, Eastern Time, until we went out to Earl’s Court Road and saw the huge black screaming headlines “John Lennon Shot Dead “ at the news agents at the trance to the tube station.

“King Richard’s Court Hotel” didn’t service breakfast on Sunday mornings. It was the staff day off. We were allowed, within reason, to use the kitchen. Sometime in the middle of that winter of 1981 “Darren” and I were longing for something Canadian. We went to Harrod’s basement and bought pricey pancake mix and maple syrup and made pancakes. Jill asked to join us, then others did. On many Sunday mornings, we cooked up a batch of pancakes for the gang. (After I retired, I remembered that old ritual and now on many Sunday mornings I have pancakes for breakfast).

Our room with three single beds was on the top floor. Whenever we didn’t have a roommate in the third single bed, which was quite often, “Darren” and I had the room to ourselves as if we were living in our own flat. We had sex at every opportunity. I am sure “Broomhilda” knew it and at least in the winter, didn’t care.

Eventually we did have a third roommate who also became a long term resident, Peter, a straight Australian from Brisbane, who quickly figured out we were gay partners, who didn’t care that we were gay and became a friend who accompanied us often to London’s more straight fun opportunities. He made himself scarce often enough that “Darren” and I could enjoy our sex lives without worrying that we would be interrupted.

It was our Aussie friend who eventually got us kicked out. He had a girl friend named Margaret. A couple of times when they were out late, he would sneak her into our room. He slept in his sleeping bag on the floor while his girl friend slept in his bed. The second time, “Broomhilda” barged into our room at 2 a.m. clearly knowing what was up. She demanded Peter leave in the morning and that the two of us be out by the weekend. It was the second week of June. It was likely that she was clearing house for the summer tourist traffic.

Luckily, we found a new flat quickly, in Cranley Gardens, just off Old Brompton road in a rather rundown building, a fifth floor walk-up which actually had a small kitchen, toilet and bathtub. (We guessed that once it had been the servants’ quarters). The three of us moved in, knowing that “Darren” would soon have to go back to Canada, as unlike myself or the Aussie, his visa was about to expire.

The “Semi-gay Pub”

After I arrived in London, it took me about a week to get the paperwork sorted out so as a dual citizen so I could actually have no legal problems finding work. I started going to the Job Centre on Kensington High Street, searching the job boards and talking to the job counsellor.

One day the job counsellor left his office, looked at the crowd of about fifteen or so people in the waiting area. He pointed to me and two other guys and called us over to the counter. “Do you want a day’s work for cash?” he asked. We all said yes. “The baby shop across the street has just had all its Christmas goods delivered and they want three ‘good looking young men’ to unload.” Off we went across the street. Given that it was on Kensington High Street, it was an upper crust expensive store. I guess they didn’t want their customers watching as just anyone did the unloading. That was my first job in London.

A couple of days later, the counsellor told me about a job as a barman at a local pub, short term for the Christmas season, no experience necessary.

That’s how I came to work at what I call “the semi-gay pub”

It’s a small neighborhood pub just steps away from Hyde Park. That Christmas, the pub had its own cast of wonderful characters.

Back in those days, you wouldn’t have found the pub listed in any of the gay guides to London.

Why do I call it “semi-gay?” If you were the barman, then on your left hand side, where the bar curved around in front of the side door, that was where every night the pub ‘s gay patrons would gather. It was mostly the neighborhood gay “local.” Often their gay friends from outside the neighborhood would join them. The front bar is tiny, so back then the “gay corner” would take up at least a third of the space and more.

I am not naming the pub. It is still open. The pub has probably gone through several ownership and management changes in the past forty years.

UPDATE: I went back for the first time in 2017. The manager and the bar staff were somewhat surly and unfriendly to a stranger. The regular patrons on a warm Sunday afternoon were clearly enjoying themselves. I had no idea if the gay corner is still occupied in the evening, in the way it once was decades ago. The 2017 reviews were mixed. Many people loved it as a friendly local neighborhood pub, especially the Saturday and Sunday night sing-along. Others, tourists and businesspeople complained about the unfriendly staff, bad service and mediocre food.

The pub survived the Covid 19 lockdowns and I returned again in 2022. That weekend in August, was very different, a whole new staff likely due to turnover from Brexit and Covid. The staff was much friendlier, the service was better and the Sunday roast was at its British best. The online reviews have picked up as well.

Back in 1980, the manager, “Joseph” interviewed me and hired me on the spot. It was pretty obvious that “Joseph” was gay. I soon found out that he was trapped in a very British closet. Unless you owned the pub yourself, and most were part of brewery chains or owned by food management companies, you had to be both respectable and married. “Joseph” had been working at a golf course. There he met his wife, a woman who wanted to work as a chef in her own restaurant. So, apparently, they had a marriage of convenience that let them both do the work they loved.

“Joseph” hired two more bar staff a week later. One was a young Englishman named Paul, probably in his early twenties, good looking with sandy hair. The other was a young American woman who was always wearing reddish dresses and blouses.

One night on the job, after I had been working for a couple of hours, “Darren” dropped by the pub. A few minutes later a good looking, dark haired young man came in, sat down on a barstool beside “Darren” and started talking to Paul. It took us just seconds to realize that this new guy was Paul’s partner, just as they realized that “Darren” was my partner. The pub wasn’t that busy, so we all had a good laugh.

It took a couple of nights for “Joseph” to find out what was going on, which left us wondering what just had been going through his mind when he hired us.

There were about a dozen or more regulars in the gay corner.

One was an older man, probably in his mid fifties, named Allan who said he lived in a big apartment near the pub. He invited me, Darren, Paul and his partner, to check out the place and possibly stay with him in the two spare bedrooms. It was a large luxurious apartment with plenty of room and a view of Hyde Park. The rent he offered was attractive. We never moved in. Allan was an alcoholic. The next day he fell off the wagon and turned up drunk at the pub. I am now wondering what Allan’s story was, to live a solitary homosexual life in a huge empty and expensive apartment, slowly drinking himself to death, possibly a victim of Britain’s harsh homophobic laws and customs when he was a young man.

Another man was the manager of another large luxury apartment building near Hyde Park. He kept talking about his Filipino house staff, so much so that I go the impression he was probably exploiting them.

One night a flamboyant man (to use the popular term at the time) showed up in the gay corner when it wasn’t busy. He told me was home for Christmas visiting family, He worked as a hairdresser in Los Angeles. I knew that hair dressing wasn’t exactly a rare occupation in LA, so I asked him how he got a green card. “I married one,” he said, waving his hand in front of my face.

There was one man who showed up only a couple of times. He was a big man, very muscular, who sat at the exact centre of the bar, not close yet not far from the gay corner. I couldn’t figure him out. Once he spoke cryptically about security work. So, was he military, police, MI5 or a pretender? I will now never know.

There was a group of other gay men, regulars, who invited us to a couple of local Christmas parties and pub crawls.

The young woman hired as the third bar person told us she was returning from India and was earning money before returning to the United States. It is likely that “Joseph” hired her undocumented and paid her cash.

We soon found why she wore red all the time. She was part what soon became infamous as the Rajneeshpuram cult. That meant she was heavily into free love and free sex. Whenever she was working with me or with Paul behind the bar, she would always, when “Joseph” the boss wasn’t around, be stroking our backs, pushing her hips against our buttocks and far too often putting her hand into our crotches from behind. I finally told to her fuck off and stop it, but she only eased off. In some gay bars and in a bathhouse, there is implied consent to light touching that doesn’t go any farther unless you say you wanted to take it farther. There was certainly never any consent with the woman, it was always uncomfortable. It made no difference to her that both Paul and I were openly gay.

“Darren” Chapter One.

I said in the lead that London in 1981 was both happy and upsetting.

Readers may ask why I am using “Darren” when most of my surviving gay friends in Toronto know the real name. “Darren” had a straight brother a couple of years younger, who I met several times, and, if I remember correctly, an even younger brother or sister. His siblings would likely have children and even grandchildren of their own now. There is no need to know “Darren’s” real name.

It probably in the middle of the winter of 1981 that I am began find out gradually, drip by slow drip that “Darren” was not all he claimed to be He had occasional flashes of rage that quickly went away, which I see now as indications of future mental health issues.

At the same time, we were having the time of our lives in London with all the metropolis had to offer, not just the gay life but the sights, the places the tourists go, the local places the tourists seldom go, the theatre. We went to see Annie probably three weeks after we arrived once I had started to get some money from the job in the “semi-gay” pub.

“Darren” found an undocumented, wages for cash job in an off licence (that’s British for liquor store), so we were no longer dependent on just my income. His employers, a Cockney husband and wife, liked him, he was a hard worker and always charming with the customers. They applied and got a temporary work permit for “Darren.” They had us over for Sunday dinner several times.

“Darren” surprised me by buying some hard to get tickets to see Maggie Smith and Nicholas Pennell in Edna O’Brien’s Virginia at the Theatre Royal Haymarket.

Over the coming months, bit by bit, it became apparent that his aspirations for an acting career were more fantasy than reality. He only applied to only one school. He couldn’t be bothered working on his audition pieces.

When we weren’t going downtown to Heaven, we went to a popular and trendy local pub, then called The Denmark, on Old Brompton Road, where among other young people, acting students would hang out. “Darren” never tried to talk to any of them.

It was in May 1981 that “Darren” caught a cold and then complained of a pain in his neck just under the ears—the location of the lymph nodes. The cold and the pain went away. He was soon back to his old energetic self.

Lymphadenopathy can be a benign swelling of the lymph glands after a bad infection, perhaps even from a cold or it can be an indication of something a lot worse. In that May of 1981, In New York, doctors were beginning to see more gay men who were showing symptoms of lymphadenopathy, along with Kaposi’s sores, unexplained fevers, abdominal problems and stubborn colds that wouldn’t go away.

He failed the auditions (I was never certain if actually showed up).

Although London was expensive in those days (as it has been for much of history), it wasn’t prohibitively expensive. When Darren, I and our a straight Australian found the fifth floor walk up flat with a bath in Cranley Gardens in South Kensignton, it cost the three (and then two) of us £55 a week which we could afford.

“Darren’s” six month visa was about to expire. He would soon have to go back to Vancouver. I planned to stay in London for the foreseeable future.

On “Darren’s” last night in London, I took him out for a fancy dinner at a gay restaurant in Fulham. We had our usual great sex that night. The next day he flew back to Vancouver. I wasn’t sure if I would see “Darren” again but at that point I wanted to. We missed each other.

There was only one telephone in the ground floor hall of Cranley Gardens apartment building, the same number for all of the flats. Getting a call depended on the people in either of the two ground floor flats answering and then calling up to the upper floor. Coordinating incoming calls was always a guess that I would be in and if the people on the ground floor would answer and call up to me on the fifth floor. I could try to call “Darren” in Vancouver. Given the time difference often he wasn’t at home.

“Bev” who was our Jill

The other parallel in our lives with It’s a Sin was “Bev,” who sort of became our equivalent of the character Jill, at least for the glorious year 1981.

In the first episode of It’s a Sin, Jill (played by Lydia West) is Ritchie’s best friend from theatre school.

As Davies told The Guardian

We’ve known each other since we were 14, daft camp kids belonging to a wonderful youth theatre in West Glamorgan which was accidentally, brilliantly, the safest gay space imaginable. As we grew up, I went to university, got a job, started to write, but Jill lived a bigger, better life. She went to London. Became an actor. She moved into a flat which she called the Pink Palace…

In the Pink Place, Jill where becomes the “den mother” (to use the American scouting phrase used by US reviewers) As Davies says the real life Jill as one of his best friends from those days, Jill Nadler who plays Christine Baxter, “Jill’s” mother.

“Darren” and I met “Bev soon after we arrived in London. We went to the Samuel French Bookstore, in downtown London to find audition material. It was “Bev” who helped us find what we were looking for. She was an American theatre student who had come to London on a working holiday visa.

After the sale we kept chatting about theatre. “Bev” joined our circle of friends.

While “Bev” wasn’t a den mother, she was fun to be with. We’d drop by Frenches when we were in the neighborhood just to say hello. A couple of times when the bookstore staff were doing a special promotion, they were all in costume.

We usually met up with her at the nineteenth century Hansom Cab pub in Earl’s Court.

The Hansom Cab was then at the heart of a gay neighborhood. It too then was a gay local and sometimes young actors’ hangout.

“Bev” as affectionate joke gave us a copy of How to be an Alien by George Mikes. with the inscription To “Darren” and Rob As if we didn’t know” Much Love “Bev.”

We’d meet every few weeks or so until her visa also expired, and she returned to the United States. I called her once a few months after I got back to Canada. After that our lives when separate ways.

(“Bev’s” real name is quite common and her surname would have changed if she married. I tried Google and Facebook but was unable to locate any references for a woman who would now be in her sixties who might have been “Bev.”)

The job that changed everything.

After the job at the “semi-gay pub” ended, I quickly got a new job at a busy pub in central London. I had been working there for a few days when “Darren” came in just before the afternoon closing. “Darren” ordered a half pint from me and took a seat at table, waiting. At closing time, the manager asked, “Is he with you?”

I said. “yes.” The manager reached into the till, counted out some cash and told me “Get it out of here.” I was fired.

One of the reasons that I had gone to London was to do research for a book I was hoping to write. I used a reference letter that CBC News had given me when I quit to get accreditation to do research in the magnificent circular reading room of the British Library, then part of the British Museum. And yes, like many people, one day I was able to sit in Karl Marx’s famous seat.

I wanted a job with a little more stability than tending bar. It soon came up. My somewhat limited high school French landed me a job with French Travel Service, the British tour arm of the French National Railway. Société nationale des chemins de fer français.

Although the travel agency had its own dedicated mainframe computer, it was also experimenting with the experimental early British interactive videotex system called Prestel. While I never did any work with the terminals, I saw a future there.

After a couple of months, I answered a blind ad for someone interested in Prestel to work for a Fleet Street news agency. I got the job. It was with Universal News Services, the British arm of the PR Newswire. UNS was also experimenting with Prestel to send out news releases to smaller papers as an alternative to teletype. The office was in Gough Square, just a few feet off Fleet Street, across from Dr. Johnson’s House and around the corner from the famous Old Cheshire Cheese pub.

I had been there a couple of months when I spotted a story in Variety about how the Canadian government was developing a similar system called Telidon. I called the Canadian High Commission to ask for more information. The High Commission had a mandate to recruit Brits working with Prestel and were thrilled to know there was a Canadian working in the new industry. To make a long story short, a few weeks later I got a tentative offer from Southam, the Canadian newspaper chain that was also working on a Telidon experiment. “If you ever want to come back to Canada, we’ll have a job for you.”

I will write later in depth about how my forty year career in online news began with Universal News Service. My trip to London did regenerate my journalism career but not in the way anyone could have expected. By late October 1981 I was back in Toronto and at work at Southam’s Infomart the Monday after I got back in the city.

“Darren” Chapter Two

My diary tells me that I missed “Darren” in previous months although I was torn about getting back with him. As was perhaps inevitable, once I was in Toronto, I called him, and “Darren” flew from Vancouver. He joined me first in a cheap apartment on the outskirts of the gay village, one which we could easily afford. Although we both had our own bank accounts, we set up a joint account to pay for rent and utilities on the basis we would both contribute our fair share.

That wasn’t good enough for “Darren.” We soon moved into a high rise in the village. I wanted to buy furniture at the cheap used stores on King Street. “Darren” wanted something better and signed a lease with a furniture rental company.

It was in the late fall of 1981 that I noticed a news brief in the science magazine Discover, a couple of paragraphs, given the longer deadlines for glossy magazines, about the mysterious gay cancer; a story probably picked up from the original in The New York Times and the CDC Morbidity and Mortality Report.

“Darren” got a job at McDonalds. What he really wanted to do was to start a wine importing business based on his experience in London. He had no idea how to run a business, no idea about the tangled bureaucracy of the Ontario liquor regulations. None of that stopped the fantasy world he was creating. I told him he was on his own financially as far as the business was concerned. Somehow, he convinced a major bank to give him a loan—at the 1982 rates of about 20 per cent. His father, supposedly a successful businessman back in BC was no where in sight.

He walked away from the job at McDonalds without giving notice to concentrate on the wine business. At first, it looked as if things might work out just from plain dumb luck.

In a premonition and warning of what was to come in online news in the ensuing 40 years, Southam had no idea how to run an information tech start up. The company left management to hardware engineers and fast talking salesmen, who had high expectations, overpromised the handful of clients and over hired.

I was the victim of layoffs in the early spring of 1982, just as it really became apparent that “Darren’s” fantasies were fantasies. He persuaded the couple who had hired him back in London to invest. Then a few weeks as was becoming clear that the business wasn’t going to succeed, behind my back he persuaded Michael, a close friend of mine to invest, a friend who never bothered to consult with me.

Throughout the winter of 1982, there were times that “Darren” complained of not feeling well. The swollen lymph glands were back and more painful. He had a thrush on his tongue. We didn’t know it at the time but those were early signs of HIV/AIDS. I pulled out that old Discover magazine, getting worried for him, but that two paragraph story was just about all the information available.

Our relationship began to collapse when “Darren” decided he wanted to buy a house at a time when we could barely pay the rent on the apartment much less the furniture he was renting.

He used his charm to get a job in ad sales for an upscale magazine. After he had worked three days, I got a call from his boss. He hadn’t shown up. We were back with our finances dependent only on me. I told him to get a job, or our relationship was over.

I found out it was already over. “Darren” had started to have an affair with a guy named Terry. We began the process of splitting up.

“Darren” caught what appeared to be a bad flu. It was winter. He recovered.

“Darren” was spending more time with Terry. I was looking for a way to move out.

By early March 1982, there was little information about what was to be called AIDS available. History now shows the first Canadian case was officially diagnosed that month March 1982. Larry Kramer published his famous warning “1,112 and Counting” in the March 12-27, 1982 issue of the New York Native.

On April 5, 1982, “Darren” got really sick. He had a high fever, no energy and a thrush on his tongue. He broke out in spots, which we were told were “fever mottles” the type that are usually found in babies and young children with a bad infection.

He saw a doctor who admitted him to Toronto General Hospital. At first, he told me that had an enlarged spleen and “a low blood count.” When I visited him a week later in the hospital, he said it was just a mild pneumonia.

After he was discharged, he still wasn’t feeling well. There was a potential problem. When “Darren” was working at McDonalds, he had been paying Ontario provincial insurance premiums . Since he hadn’t worked in a couple of months, that meant his health insurance would soon expire.

I called his mother; told her he was sick. I suggested that he should go home to Vancouver where he could live at home, his mother could update his BC health insurance and he could be treated. I did want him to get better. It was also a diplomatic way of ending the relationship. His mother bought an airline ticket.

While he was away, I called the rental company and cancelled the lease on the furniture. I was able to quickly sublet the apartment and prepared, rather reluctantly, to move back with my father.

Then came another phone call from his mother She had taken “Darren” to her family doctor in the suburban Fraser Valley who likely had never heard of Gay Related Immunodeficiency Syndrome or GRIDS. GRIDS was a term that was only weeks old, adopted in New York on January 4, 1982. AIDS was even newer. The doctor said there was nothing wrong with “Darren.” I was the bad guy.

This was in the same weeks that Larry Kramer wrote from the epicentre, New York “For the first time in this epidemic, leading doctors and researchers are finally admitting they don’t know what’s going on.”

I was also the bad guy in Terry’s eyes. He had dropped by the apartment was I was cleaning it out. He was preparing to fly to Vancouver to join “Darren.” I tried to persuade Terry to be careful, specially about money. Of course, I was the aggrieved ex lover.

In July, “Darren” called me from Vancouver to say he had “leukemia.” He was living with Terry.

In mid -October, he called me again from Vancouver to say that Terry had beaten him up and kicked him out of their apartment.

In mid-November 1982, I ran into Terry as he walked up Yonge Street. “Darren” had cheated on Terry with another man and had also taken some of Terry’s money. Then “Darren” had stolen money and a watch from his new love interest and had disappeared. Terry thought “Darren” was in Seattle.

On Dec. 2, 1982, “Darren” called me from Waikiki. In a rambling phone call, he said he was drunk and high on cocaine and that he missed me. Then he hung up.

I never heard from “Darren” again.

In the following year, Terry was working as a barista in a popular coffee shop in the gay village, his face covered in Kaposi’s sores, which in the village in 1983 and 1984 you didn’t have to hide to keep your job. After that I never saw him again.

When Michael told me that he had given “Darren” so much money I was enraged and lit into him for not even asking me if it was a good idea. That caused a five year rift where we seldom talked until Michael called one day to say that he was dying of AIDS and was making up with people. Michael invited me to his “goodbye party,” which was almost as wild as the parties he had hosted in the late 70s and early 80s. He died in 1988.

The AIDS crisis begins

That Telidon job did come through. I was back at the CBC, working in the experimental online newsroom called “Project Iris.”

In March 1983, Toronto activists founded ACT, the AIDS Committee of Toronto.

One of the staff, a casual acquaintance, spoke to me, saying “We need all the information we can get.”

The Toronto media coverage was mostly sensational and hostile. For the next two years, until Project Iris was cancelled, whenever I was at work, I kept my eyes peeled on the wire service machines (which had just transitioned from the old clunky teletypes to dot matrix printers) and harvested any story on AIDS (GRIIDS had been renamed in the fall of 1982) and took the sheets of newsprint to the first ACT office above a Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet.

Jim Jefferson who had helped ease my way into Gay Youth Toronto became an award winning legal reporter for The Globe and Mail.

He became fascinated by the law and decided to become a lawyer. Just as he was graduating from law school, he was diagnosed with AIDS. The Globe and Mail supported him with a job on the copy desk until he became too ill to work. (pdf) In the late 80s we had lunch when ever we could.

On November 27, 1991, Mark Whitehead, the founder of Gay Youth Toronto called me to tell me that the previous day Jim had had a sudden seizure and died.

In It’s A Sin, there is a scene when the audience is shocked as the innocent and naïve Colin Morris-Jones (played by Callum Scott Howells) is found on the floor after suffering an unexpected seizure while working in a printing shop.

I had steeled myself for anything else I might see in It’s A Sin. Seeing Colin lying on that floor was the only scene that got to me. The seizure came as a shock; it was the hardest to watch.

Olly Alexander’s excellent performance as Ritchie Tozer is combined with Russell T. Davies writing makes It’s A Sin as masterpiece. I saw in Ritchie probably a dozen or more guys I knew the late 70s and early 80s. I danced up a storm with many Ritchies at the Manatee at 3 am on a Sunday. Always the science writer, in the mid 1980s I argued with my Ritchie friends about AIDS. I went to too many funerals in the years 1991 to 1993 (In the series, Ritchie dies in 1991).

There’s probably a little of Ritchie in me as well. Sometime in the summer of 1992, I saw one of those funeral notices for a friend I hadn’t heard from for a while. He was originally from Seattle and had moved to Toronto in the early 80s. The location was in a church I had never heard of.

The “church” wasn’t easy to find at first. It turned out to be a tiny Catholic chapel attached to a homeless shelter. There were about ten men at the service. No family were present. I had never slept with the man who had died, he was “just a friend.” To my shock, I had had one night stands with four of the men at the funeral, during the early days after I came out in 1977. I had met every one of them at the Manatee.

What happened to “Gordon” and other friends.

In My Own Private Oshawa, Jonathan Wilson tells how “Gordon” moved to Toronto. Jonathan didn’t see “Gordon” much after that even when he too moved to Toronto. As he says in My Own Private Oshawa, they talked on the phone, promising to get together but never did.

After I split with “Darren,” I was enjoying being single. It was in December 1985 that I took my then boyfriend to a Christmas party at a friend’s apartment. It was there, as far as I recall, that I first met the young man with the quirky smile who Jonathan Wilson would later wonderfully portray as “Gordon” in My Own Private Oshawa.

I usually go for guys my height or a little shorter. As well as the blonds I mentioned, I also find dark black hair almost irresistible. As happens at parties, a group of us gathered in the kitchenette in the apartment. All the guys but me had dark black hair. That’s when “Gordon” quipped. “Well, we now know what Robin goes for don’t we?” That brought a big laugh and endeared me to “Gordon” for the next few years.

Another time I remember is that a group of us were in a dance bar. One friend spotted a good looking man and said, as a joke, “Fetch.” Which “Gordon” immediately did, bringing the man over to our group.

“Gordon,” was a lively lovely man, always with a sense of humour.

“Gordon” got sick. As Jonathan recounts he called “Gordon” to finally arrange to meet. “I’d love to,” “Gordon” replied. “But I have this condition.”

One day a group of his friends were gathered around his hospital bed. I was there, A young man we didn’t know, probably in his early thirties, came in. He mentioned that he was a hospital chaplain.

Everyone stared at him. It was just like in the old comic books when the artist drew daggers from our eyes toward the man. He fled.

Gordon was released a few days later. He told everyone it was a misdiagnosis. Like Ritchie’s denial, of course it wasn’t. He had AIDS.

After I hadn’t heard anything about “Gordon” for some time, I called one of my friends. I wanted to see him. “You can’t,” he told me. “His sister is taking care of him and won’t let anyone see him.”

Just like Ritchie’s sister and parents in It’s A Sin.That barrier finally broke when “Gordon” had to move to the Casey House Hospice.

I finally got to visit him and saw him sitting up bed with his big, gorgeous smile. There were two things he told me. One was still denial. “I’ll only here until I get better.” The other was acceptance. “I’m taking mass every day,” a complete reversal from the day when we silently drove that poor chaplain from his hospital room.

At the funeral scene in the movie, Jonathan says to Gordon in the casket. “Your parents completely ignored me of course. Maybe they don’t remember me. Your sister was eyeballing me though. You can almost hear her whispering back there. ‘Leave my brother alone. He’s not like you.’”

I didn’t hear about Gordon’s death until a few weeks after the funeral. Jonathan, being from Oshawa, managed to go and that is the closing scene of the play and the movie. Most of “Gordon’s” friends were not notified and not invited, just as Ritchie’s friends are barred from saying goodbye and from Ritchie’s funeral.

In 1996, My Own Private Oshawa premiered at the Toronto Fringe. When I sat in the audience, I watched a pretty good play in a series of AIDS related plays. Better, in fact, one that finally did not take place in New York like all the others that I, a theatre lover, had gone to see. My emotional barrier wall held. It was nothing personal. After the performance I went backstage to congratulate Jonathan. We were chatting and he said “Gordon was C—. Did you know him?” That struck me like a ton of bricks.

I rewatched My Own Private Oshawa so I could write this, just days after I had watched It’s A Sin. My gut is tied in knots from both shows.

Too many funerals

Like many gay men I eventually stopped going to all but the most critical funerals.

I did go to for a funeral for friend named David. At the service, a family member mentioned in the eulogy that David had wanted to hike Samaria Gorge in Crete. David did that hike with a brother before he got too sick.

A man I had unsuccessfully tired to pick up at the Manatee way back in 1978, but who became a friend instead, was now living in Crete. So, twenty years after I first met him, in 1998, I went to Crete as part of vacation and research trip for more writing. I have been nuts about ancient history since I was probably ten years old. I hiked Samaria Gorge, both because I have always liked to hike and in memory of David and all the other friends who had died.

The one funeral I wanted to go to but just couldn’t make the connection was for my friend Stephen. I had met Stephen 1989, at Noreascon 3 in Boston the world science fiction convention.

We became friends over two mutual interests, science fiction and world travel. In the early 1990s, Stephen’s partner became ill with HIV. He quit a lucrative job to care for him. At the time, I was attending the Literary Journalism conferences at Boston University, staying in a bed and breakfast and going out for dinner with Stephen.

His partner died. I kept coming to Boston at least once a year for the conference. I slept in Stephen’s spare room, attend the sessions and we would meet and go to the clubs. It was during one of those visits that he told me he was HIV positive.

In January 2004, he sent me an email saying how much better he was feeling. It was in late June 2004. I was just opening the door of my house to go out to a Pride dance. The phone rang. I turned around and answered. It was Stephen’s new partner calling to tell me that Stephen had died. I didn’t feel like staying home. I went to the dance but couldn’t do anything more than stand in a corner and stare out at everyone having so much fun.

The years passed. Most of my friends who are HIV negative were already in monogamous relationships before the plague arrived. Most of them are now legally married. Others survive on the AIDS cocktail and its successor medications. I still worry about them.

Back in the 1980s, once an HIV test was available, we were advised, just as you see in It’s A Sin to get tested every few months. My tests were all negative. As I got older and was a lot less active, I stopped getting the regular tests.

I retired and moved back to my hometown in northern British Columbia. I love the wilderness. I was getting older in my late sixties. I had to have a cataract operation. About a week or so after the operation, the hospital called. One of the nurses had accidently pricked a finger. Could I come in for an HIV test. I did. I went through the usual check list. Have you ever had sex with men? Yes, many times. Three days later, the results came back. I am still HIV negative.

Just before I left Toronto, I was having a drink with an acquaintance in a bar who was with his rather plain spoken partner at the time. At one point the partner turned to me and said. “Why are you still alive?”

I can’t answer that question. I am alive and I had to tell this story.

The captain (RN retired)

There’s one other customer I have to mention, an elderly gentleman, friendly and personable, who was one of the most popular people in the “semi-gay pub.”

James (his real name) was probably straight. He sat his regular table not the gay corner) a white-haired retired Royal Navy captain with a big smile. The captain had throat cancer. He was considered a bit of an English eccentric because he kept his own personal pint mug that he believed no one else should use—because he had throat cancer.

“Cancer isn’t contagious” everyone said. I was filling up the captain’s pint mug one night and as I handed him the beer, James must have known I was curious.

“You just have to be careful,” James said shaking his head. “You never know. You have to be responsible.” (or something like that( In retrospect I am sure he was referring to his role as a captain in the Royal Navy who has the ultimate responsibility for the lives of his crew. He must have been in his late 70s or even early 80s, which means likely be had served in the Second World War. When James was at his usual table and when “Joseph” called “Time please,” signalling the pub was closing, he would drain his mug and then leave, giving everyone a friendly wave with that mug as he went out into the night.

“You can’t catch cancer….it’s not like a cold…It doesn’t transmit. How is a cancer contagious?” Ritchie tells his flatmates and friends as they walk through under the railway arches of London’s Charring Cross in It’s a Sin, heading for the hottest dance club in the UK, Heaven. That monologue on cancer brought back memories of Captain James.

Just a couple of weeks after I met the captain, in New York City, in early January 1981, Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kein, a cancer specialist at New York University Medical Center would see his first young male patient with the rare cancer called Kaposi’s Sarcoma as well as other problems including weight loss, fever and hardened lymph nodes. It was six months later that Friedman-Kein would call The New York Times. The story of the mysterious cancer affecting 14 homosexual men, now considered the start of the HIV/AIDS pandemic appeared in the New York Times on page 20 on July 3, 1981.

On that July day in London, there was a race riot in Southall. Rioting that would build and spread across Britain that month. Apart from the riots, and Margaret Thatcher’s harsh reaction, one story dominated the news, the coming wedding of Charles Prince of Wales and Diana Spencer on July 29.

“Cancer isn’t contagious”: was heard among my gay friends in the early 1980s.

“You never know. You have to be responsible.” I have never forgotten James the captain, mainly because he was one of the nicer and more memorable people I met in that year in London.

Now 44 years later, if this were one of the fantasy stories I now write, instead of a harsh reality, the captain would be the wise Elder, the threshold guardian, warning of what was to come. “Be responsible,” he said, even though there was minimal danger of catching cancer from a glass mug.

“Be responsible” became a watch word in the gay community, quietly and slowly at first, trying to cut through the denial then louder and louder as we knew more from personal experience and the progress of science and medicine. But no thanks to the political, religious and many in the medical establishments, the LGBTQ community had to do it ourselves.

That is why today while Covid-19 is still killing people around the planet. I get enraged when far too many are partying as if the pandemic is over. Even worse are those who say Covid-19 is nothing more than a bad flu or the conspiracy theorists who smile at TV cameras and say it’s all a hoax.

They haven’t seen their friends die one after the other.

There are those conservative politicians, mostly in the US Republican Party, but elsewhere as well, who refuse to enforce mask mandates, who open up businesses wide open, disregarding the still growing cost of Covid-19 in human lives. These are the same political parties and even some of the same politicians who did little or nothing as AIDS was spreading.

That’s why I today I salute the captain. I’d love to see a statue of the old gentleman, in civies of course, raising his pint mug as a lesson to the world.

I wish I could find out more about Captain James and his possible naval service in the Second World War. Unfortunately my diary didn’t record a surname. It was 1981, so even if he was in his late 60s and it is more likely that he was closer to 80, he must have served. I wonder if his sense of responsibility regarding the pint mug has its roots in the war

It’s A Sin and the Reviewers

It is obvious that It’s a Sin has made a profound affect on me. It compelled me to put aside the science fiction novel I am working on for a week or more to write this.

When the story is about what you experienced, you go into a theatre for a play or a movie or turn on the television and wonder, first of all, has Hollywood fucked it up? Or did they get it as right as you can when you’re producing a work that has to also appeal to a wide, usually commercial audience?

I did lead a parallel life to the story. I can’t say enough to praise Russel T. Davies writing. Olly Anderson is near perfect. I wish I could I call some of those old friends and say “Did you see him? He was you.” Anderson is also doing what they call in acting classes, “playing your fairy tale,” channeling his own experiences. If The Doctor could take Anderson in the Tardis back to Heaven on the night I was there August 9, 1981, he would fit right in. If I had been lucky enough to spot him in the huge sweaty crowd, I would have asked him to dance. (Tardis technically we would both be 30).

Some of the reviews from both the critics and activists have taken issue with the portrayal of the women, especially Jill, and the Black community, mainly Roscoe, who they say weren’t fully realized as characters.

For those I have two answers.

First most of you weren’t there.

The old advice of writing about what you experienced and what you know holds true. You write about the people you knew, your lovers, your friends, the activists, the people you met. In the gay community of the 1970s and 1980s for me that was mostly other white men. Writing about what you experienced in a situation like the AIDS crisis can be so exhausting and also liberating at the same time.

Writing a story or script that is both painful and personal never lends itself to checking boxes whether it was the infamous censoring Hays Code in the middle Twentieth Century which completely excluded LGBTQ2S characters and storylines or some 21st century postmodern professor born long after the AIDS crisis who draws up a list of what and who to include.

Second this isn’t the Marvel Cinematic Universe where you can reboot and regenerate characters and make the story line more inclusive and more exciting at the same time.

There should be more fictional films about the AIDS crisis told by diverse voices and not just the Black community that is so often mentioned in the reviews. (There are numerous documentaries)

In Canada there is currently an explosion of amazing work by indigenous film makers.

For those who may not have seen it, I strongly recommend the 2019 indigenous zombie/ horror/plague/ movie Blood Quantum which is available on some streaming services.

The film maker Jeff Barnaby, who is Mi’kmaw from Listuguj, Que, has said Blood Quantum is a metaphor for environmental catastrophe. as well as the long history of colonialism.

Two aspects of Blood Quantum stand out. First, like It’s a Sin, the film opens in 1981. (Barnaby says it took 13 years to write and produce). Second, in the gory film, the zombie infection is passed by blood first from salmon and dogs to humans though bites. Indigenous people are immune, others are not.

The HIV/AIDS crisis has had and is still having a devastating affect on indigenous communities across North America, communities that have been hit by plagues in the past, smallpox, measles, the 1918 flu epidemic and now Covid-19.

At the same time, the other indigenous films I have seen also have an underlying humour and humanity similar to what we see in It’s a Sin.

The problem is financing. Even someone like Russell T. Davies with his successful track record had problems getting It’s A Sin produced. It’s a Sin was turned down by both BBC and ITV. Channel Four had to put it on hold, then commissioned a five part, not an eight part series. One can only wonder if Davies had been able to produce eight parts if the characters of Jill and Roscoe, which some critics say are a weak point in the series, would actually have been further developed. It’s a Sin also required an American star, Neil Patrick Harris and a British star, Stephen Fry to help secure the needed money.

The competition among the streaming services ( for now until they inevitably amalgamate) provides a window of opportunity in an era where diversity and inclusion are becoming crucial. So, such films could be produced. Commissioning producers I hope you are reading this.

I recently attended a Zoom conference for LGBTQ2S science fiction writers. One thing that I heard over and over again is that our community is sick and tired of just watching trauma and tragedy. The conference took place before It’s a Sin was widely available in North America, so the series wasn’t mentioned. In my view, It’s a Sin strikes just the right balance between joy and sorrow.

There is one otherwise good review of It’s a Sin that in the end doesn’t get it. HBO’s It’s a Sin is a Radiant Coming-of-Age Story in a Dark Period. Nick Allen at RogerEbert.com.

takes issue with the final episode where he writes

Take the final episode, which repositions the focus onto a family member who had been mostly off-screen, facing the sickness of their child. It’s an admirable attempt to expand the scope of the story, and focus it on the damage of shame, but it does not have the same natural storytelling as earlier passages. You never want to feel aggressively forced to cry for a character who is sick in bed, and the final episode of “It’s a Sin” hits that note a few too many times.

The trouble is that real life often doesn’t fit in to a convenient on screen story arc. As the fictional Ritchie died, as the real life “Gordon” died, the focus of their story did change to the family members who had been “mostly off-screen,” who were suddenly “facing the sickness of their child.” That off stage story happened thousands of times around the world, to “too many” of my friends who went home to be “sick in bed” until the last. For me, the final episode hit the exactly right note.

One last arrow aimed at the critics who weren’t there at that time. There was similar criticism about Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk, because that movie also didn’t check off an inclusion list. Unlike many war movies, it was the surviving veterans of Dunkirk who told reporters that Nolan got it right. Those veterans were all nineteen and twenty year old kids at the time (the same age as the characters in It’s a Sin).

When 97-year-old veteran Ken Sturdy showed up at press screening in Calgary, his reaction was ““I never thought I would see that again. It was just like I was there again.” That story went viral around the world

Veterans who talked to People magazine emphasized how important it was for young people today to understand what they went through and how Nolan succeeded in doing that.

It’s a Sin gets it right. I was there.

Critical points