Two hunters from “Downton Abbey” came looking for bears in Kitimat, Kemano and the Kitlope in 1908

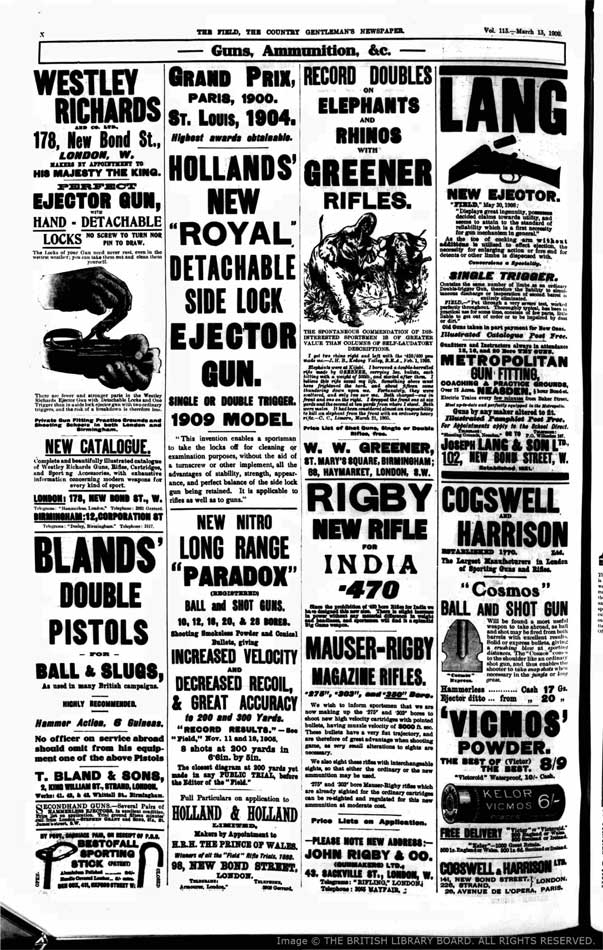

Masthead for Field in March 1908

In May, 1908, 114 years ago, two presumably rich, presumably British, hunters came to Kitamaat Village, hired two Haisla guides named “Frank” and “David” and went bear hunting in the Kitlope, Giltoyees and up the Kemano River.

One of the two hunters, named John H. Wrigley, would later write an account of his adventures which would appear in the British magazine Field The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper in March 1909.

That’s why I titled the story Downton Abbey, for the subtitle “Country Gentleman” and its many pages of ads for country estates certainly gives an indication of who the people were who subscribed to Field, 113 years ago.

A couple of months ago there was a Facebook post about a gift “the Kitimaat Indians” had given to Queen Victoria in 1898. I am working on an unrelated research project and so I have a subscription to the British Newspaper Library archives . I wanted to see if I could find any more information about the “gift.”

The people from Kitimat and Kitamaat who responded were doubtful about its accuracy. What I found was that at least two dozen newspapers in Britain ran the same one paragraph story with no further confirming information. I had thought perhaps the gifts were presented to Queen Victoria on the occasion of her Jubilee in 1897 when people and towns and cities across the then British Empire were presenting gifts to the Queen. But these stories appeared much later in September 1898, which casts more doubt on that story.

What I did find was the two part series in Field about hunting in the Kitimat region that appeared in the on March 13 and March 20, 1909.

I have been unable, so far, to find out who the author, John H. Wrigley was. His byline doesn’t appear anywhere else in the database. There is internal evidence in the hunting article and one on fishing I will post later that he was British. (For example he uses the Scottish term “gillie” for fishing guides)

The Kitimat and Haisla readers will see how accurate the descriptions are of this region.

I have retained the original spelling of Kitimaat. Wrigley used Kitlobe which I have changed to Kitlope. The paragraphing has been changed for easier web viewing.

Both articles constitute a long read.

One note. The account was written in 1909 and reflects the attitudes of the time. It was an era when a British hunter in India could boast of killing two dozen tigers—tigers are now an endangered species.

The hunters in 1909 are not satisfied with taking one bear but several.

Today hunting black bear in BC is limited by licencing regulations, seasons and bag limits (and frowned upon by many people) and grizzly bear hunting is banned in BC. Wrigley, like his contemporaries believed that BC “It is a country that can never he shot out.” By using that phrase he must have known that there were already places that that had been ”shot out” including presumably Great Britain itself.

The best example is Wrigley’s description of how plentiful the oolichan were in1908 when he went up the Kemano River. Now the oolichan are now threatened or endangered.

FIELD, THE COUNTRY GENTLEMAN’S NEWSPAPER. Vol. 113.

Saturday 13 March 1909

SHOOTING. BEAR HUNTING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA I.

KITIMAAT, OUR LAST LINK WITH CIVILISATION — now an important Indian village, and a tempting location for the many land speculators who are following the construction of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway lies at the mouth of the Kitimaat Valley, where the wide river of the same rank drains into the sea.

Southward, northward, and westward are the interminable labyrinths of the Northern British Columbian fiords, wide sea-water channels of varying width, in most instances uncharted and absolutely unexplored.

For a thousand miles this western seaboard of Canada, from Puget Sound up to the much-debated Portland Canal, is scored by innumerable inlets. studded by an amazing archipelago of islands of all mixes and seamed in every direction by the intricate waterways referred to.

Our route took us up the wild and desolate Gardener Canal, two hundred miles off the beaten track of the coasting steamers on the Alaskan run—a weird, forbidding country, but seldom visited by any white man, save the wandering timber cruiser or mining man; a country of stupendous mountains rising sheer from the sea, with half a dozen isolated valleys draining a vast extent of the unexplored ranges of the The extreme inaccessibility of this portion of British Columbia has no doubt much to do with the numbers of both black and grizzly bears that are still to be found there.

It is a country that can never he shot out.

For six months in the year these densely timbered mountains amongst which the bears live are for all intents and purposes impenetrable; then for a few weeks an occasional chance may be obtained, when the animals forsake the forest uplands for their coveted diet of salmon from the overcrowded streams, and then away they go some hole or corner in the rocks, where they drowse away the winter.

With the advent of spring. however, there is a short, indefinite season of a few weeks’ duration, best defined as the period between the departure of the snow from the low ground and the hasty growth of foliage on the cotton-wood brush, when the bears forsake their dens, still fat and ravenously hungry, to feed on the open ravines and hillsides, bared of cover by the avalanches of former years.

Here the bears find a sparse growth of vegetation in the sheltered corners, which forms their diet.

As the spring comes but slowly and the sun has but little power, save for an hour or so at noonday, this vegetation is but scanty, affording only a semblance of a meal to the overpowering appetites of the hungry animals. This forms one of the chief difficulties of the stalker, for his quarry is constantly on the move hunting for grass.

We picked up our Iwo Indians at Kitimaat, Frank and David, two of the best hunters in the tribe of Kitimaats, who bad been with us the previous season. Such eyesight as these men possessed was little less than marvelous; the ease with which they could distinguish the black outline of a bear against a far distant hillside bordered on the miraculous, and it was only to determine the nature of the animal they had spied—grizzly or black bear—that the services of a spyglass were requisitioned.

From Kitimaat to our destination at the head of the inlet, a distance of two hundred miles, we were lucky enough to obtain a welcome lift in Lieut.-Governor Dunsmuir’s big tugboat Pilot, which we found awaiting us at the wharf.

This great convenience saved us many days of arduous canoe work, for Gardner Inlet is notoriously storm-tossed, and devoid of sheltered anchorages to an alarming extent. We steamed all day up the successive reaches of this wild, forbidding expanse of landlocked water. with great mountains rearing their gaunt, snow-clad sides sheer front the water’s edge.

We took Frank’s big canoe slung in the davits, for it was upon this craft we proposed to spend the whole of our time after the Pilot left us.

Arrived at the head of the inlet, we found the conditions even more wintry than they had been nearer the tidal influences of the Pacific, and after a consultation with the Indians we reluctantly had to confess that our chances, for fourteen days at least. seemed to be very problematical.

We anchored that night off the mouth of the Kitlope River in the midst of a snowstorm that obliterated every landmark. The only sign of human habitations passed during the day had been the empty houses of the considerable Indian settlement at Kemano, a village picturesquely situated on a pine-clothed sandbar at the mouth of the Kemano River. twenty miles from Kitlope, at the head of the inlet., and eight or nine hours’ steaming from Kitimaat.

The place was entirely deserted by the Indians at this season of the year, owing to their annual harvest of a small fish known as the oolichan, or candle-fish, an oily, flabby, smelt in appearance, deemed a delicacy by a British Columbians and coveted beyond all else by those fortunate tribes of Coast Indians who have an oolichan river in their vicinity.

This fish runs up all the Gardner Inlet streams during May in numbers too great to permit of even a hazy estimate; as the tide recedes countless millions are left stranded on every sandbar, a bounteous feast for noisy, querulous gulls, crows, divers, and eagles.

This amazing waste of fish life became very obvious to our olfactory nerves as we approached the mouth of the Kitlope River next morning, determined to pole up a dozen miles to the Kitlope Lake to ascertain whether the country farther inland was yet clear of snow and huntable.

It took us nearly four hours to reach the temporary camp of the Kemano Indians, some three miles up stream, where we found the whale tribe of the Kemanos busily boiling down tons of oolichan in rough cedar-wood vats constructed on the banks of the et am. Two of the tribe had only returned from the lake that morning, and reported it still frozen over and hunting out of the question, but we decided to go and judge for ourselves.

For a mile or so below the lake the river becomes exceedingly narrow and turbulent, necessitating continual use of the tow rope, in addition to strenuous work with the poles. At last, after one final struggle over the rapids that surge round the outlet, we paddled smoothly on to the still waters of this truly magnificent sheet of water, only to find that we had been told the truth, and that the bear country in the vicinity was still covered with snow.

We therefore lost no time in changing our plans, glided down stream in as many minutes as it, had taken us hours to get tip, and were soon on board the Pilot, bound for Kemano and the subsidiary valleys thirty miles lower down the main inlet.

The Pilot left us at Kemano next morning and proceeded on her five-hundred mile run to Victoria, so we cached certain amount of stores in one of the empty houses at the village and loaded up the canoe with sufficient to last us for a forthright.

Then we hoisted the big spirit sail and ran down some half-dozen miles to a group of bare “slides” and open country known to our guides as likely bear ground.

The glasses were hardly out of their case when I heard the two men excitedly whispering to each other: ‘There he is! there he is!” Sure enough. we soon bad the glasses focused on a black bear grubbing amongst the rocks 500 ft. or above the water.

Having won the toes for first stalk, Frank was not long in shoving me ashore in the canoe.

We had an awesome climb, for the first 300 feet or 400 feet consisted of a sheer rock wall that overhung the water with only a narrow cleft. along which we gingerly picked our way upwards until we were well above the bear. We crept cautiously down to where we had last seen him feeding, and then he must have winded us at the same instant we saw him, for in the twinkling, of an eye he had whipped over a fallen log, and we heard the stones flying as he raced out of sight downhill.

There was just a possibility we might obtain a second chance at him as he crossed a steep, rocky ravine a hundred yards below us, and. sure enough, he slow walked into view, obviously out of breath and very much scared, at less than the distance we had estimated. The first shot flicked up the pebbles beneath his hind legs, which caused such an involuntary leap out his part that even Frank’s lethargic features relaxed into the semblance of a smile. The bear then scrambled along the opposite side of the ravine, feeing us, every now end then stopping to lower his twinkling back eyes in our direction while we prepared for a second shot. Momentarily he paused and the Mannlicher sights were levelled steadily against the white star on his chest. At, the shot he rolled over and over downhill until he fetched up against one of the many boulders choking the bottom of the ravine.

Wo were now beside him and found him to be a fine male in superb e – at. and obviously only a few days out of his den. A bear skin in May is a vary different trophy from the dilapidated specimens obtained late in the summer or the early autumn.

This beast was literally rolling in fat, in spite of the fact that beyond a handful of uninviting grass his body contained no signs of other food.

We soon had him skinned, and packed his skull complete, downhill to the canoe.

For two days we hunted the many excellent slides in the vicinity of the Brin River Valley, one of the principal subsidiary valleys that drain into Gardner Canal; but the wintry conditions that still prevailed proved prejudicial to our chances, and we passed much excellent bear country that would not otherwise have proved blank.

From our camp at Brin River, we hunted the slides to the northward without success until the evening of May 5, when David spied a fine black bear high up on the face of the mountain above us, feeding restlessly from the successive couloirs, where faint traces of greenery offered the possibility of a meal.

We had a good look at him through the telescope. He was a much heavier bear than our first one, and, like his predecessor, in perfect coat. He was, as David told us, very restless, for in between the mouthfuls of grass he snatched from each little bench or gully he literally ran on to find his next mouthful. He was fully half a mile uphill above us, close under a sheer rock wall that fell precipitously from the glaciers and infields above, the ground between us, though steep in all conscience, being fairly open, and covered with strips of burnt and fallen timber.

The rock wall, the home of ravens and eagles, was topped by miles upon miles of snow. We waited until the animal fed down wind behind a corner of the rock wall, and then away we went after him. It was a matter of small difficulty picking up his tracks and following cautiously along them, for everywhere he bad left very evident traces of his overpowering hunger—great tussocks pulled up bodily and hurled on one side as unsavoury.

Frank now advanced with even greater caution, and peering over a boulder in front of us, we saw our bear grubbing away at the roots of scone cotton-wood bushes, his body half hidden by the stem of a withered tree. Then lie moved his shoulder into full view, and a second later it was pierced by a Mannlicher bullet. No one could mistake the thud that was heard, although he galloped away downhill with apparent strength and speed, when suddenly he collapsed and fell head foremost into a dense patch of cotton-wood brush. He proved to be a. very big bear, two feet. longer than our first one, and again we found it impossible to exaggerate the excellence of his coat—black, deep, and glassy, with no trace of any worn patches.

John H Wrigley

FIELD, THE COUNTRY GENTLEMAN’S NEWSPAPER. Vol. 113.

Saturday 20 March 1909

BEAR HUNTING IN BRITISH COLURBIA.–II.

FROM THE BRIN RIVER VALLEY we moved on, with a favourable slant in the wind, to a very beautiful inlet on the western side, unmarked in the latest Admiralty charts, but known to the Indiana as the Inlet of Gilt-to-yeas.

Here we found slides extending over a mile of country, a well-known haunt for bears at this season of the year, but still covered with snow, with green strips of grass along the edges of the ravines.

We left camp early in the afternoon of our arrival at this glorious land-locked inlet, in plenty of time for a good spy and au evening stalk, nor had we to wait more than half an hour under the shadow of the trees on the side facing the bear ground before a large black bear stepped into the sunlight on a knoll 500 ft. above the water. He was three-quarters of a mile away when we first saw him and looked immense. We watched him walk down to a narrow torrent of snow broth, where he drank eagerly, and then we sent the canoe flying across the inlet as fast as four pairs of arms could make her go.

Directly her keel grated on the rocks we were ashore and off uphill after him. The wind had died away, and it became intensely still. At last, we stood on the plateau, within fifty yards of where we had last seen our bear, and, glancing downwards to the canoe, could see an oar held vertically in the direction of camp, telling us that our bear was ahead of and above us, though still invisible to us. With rifle at the ready we cautiously approached the clump of trees indicated, and were actually within fifteen yards of the beast, when with an angry cough he was gone.

Regrets were useless; we rushed to the highest point near in and could follow his track through the brush by the swaying of the branches. but he never gave us the slightest chance of a shot. We spent several days at Gilt-to-yees, but owing to the mild weather our chances were ruined by the thunder of continual avalanches, keeping game on the move and bears in the recesses of the forest. Day and night one beard a continuous roar as thousands of tons of snow fell ceaselessly in all directions.

From Gilt-tu-yen we moved back thirty miles to Kitlope, at the head of Gardner Inlet proper, in the hope that the fortnight’s interval might have brought fairer weather.

We took up our abode in a deserted Indian hut at the mouth of the Kitlope River. On the afternoon of our arrival, we separated for the evening hunt, my companion watching some excellent slides at the junction of the Kitlope and an unnamed river that evidently drains the country to the northward and eastward of the Kitlope, while I took the Indians and the canoe to watch all the country for a mile down the west aide of the inlet.

We were soon afloat and had not rowed a furlong before the men sighted a bear on some narrow slides about a mile away. He was feeding close to the water, so we had to use the utmost caution.

As we came nearer, he would stop feeding occasionally, looking anxiously in our direction, and, though a bear’s eyesight is his weakest point, we rested on our oars until he again set to work munching great mouthfuls of grass from the openings among the trees.

What little wind there was favoured us, and we were soon ashore, immediately below the strip of covert in which he was feeding. The avalanches in this particular section of the mountains had cut the forest into consecutive strips of covert, leaving regular rides between each section, just as clean cut, and bare of timber or undergrowth as the rides in any English game covert.

Frank noiselessly stole up the slide where the bear bad last been feeding in case he broke back, David and I taking the next one where we imagined ho might next emerge.

Five minutes, ten, twenty passed. A twig cracked, and out he came into the sunlight less than forty yards away, a glorious spectacle of a wild animal at home. He never saw us, as we crouched beside a log.

The sun shone straight into his eyes and appeared to daze him, so I drew a bead on his broad shoulder and let him have it. It was the easiest chance imaginable, and no duffer could have failed to take advantage of it. This, our third bear, had a coat every bit as fine as his predecessors, and in size ranked a little smaller than our second.

Rowing home in the twilight we watched a Kemano Indian stalking a small brown bear on the hill above us and were greatly interested to see the stalk end in the discomfiture of the Indian and the bear galloping a mile away over the distant snowfields.

We hunted in the vicinity of the mouth of the Kitlope River for at least ten days, and saw during that time at least a dozen bears, some of which doubtless were seen twice over.

With the Kitimaat and Kemano Indians May 14 is deemed the first day of bear shooting from the fact that the average spring is so timed that the date in question is accepted as approximate. Our fourth bear came to hand after many unsuccessful stalks in the Kitlope country.

We camped at the mouth of the Brin River, twenty-five miles from Kitlope, and were watching some slides in the vicinity, when, half a mile away, a big black bear suddenly scrambled to the top of a withered pine tree in full view of the canoe.

We were at a loss to account for this extraordinary behaviour when she lowered herself down again, and we went after her. The hillside at this point proved to be very precipitous, choked with fallen timber and dense underbrush , so thick that little or nothing could be seen until we climbed up a few hundred feet on to the rocky plateau where we had first seen the bear, when we paused for breath.

Below us lay the canoe containing our companions; above us a steep but narrow cleft in the rock showed us the stunted tree the bear had so recently climbed, and we crawled upwards beside a small cascade among the rocks to a point that seemed to cover the place where the bear lay feeding.

Quietly we crawled up and peered over. She must have looked up almost at the same instant, for our first shot, fired as she galloped away up the narrow cleft in the rocks, splintered the rocks ten yards ahead of her.

She turned slightly at the second bullet, lost her balance on the slimy boulders, and the next moment came tumbling bead over heels to the edge of a steep bluff, over which she fell 50ft. on to a ledge of jagged rocks below. Here she feebly tried to regain her foothold without success, and when we reached her after her second fall she was entangled in the bushes, stone dead.

Meanwhile, our voices were drowned by overwhelming cries from a small cub. This little creature we easily caught, and subsequently regaled with a mixture of condensed milk and sugar. It is now the pet of the children in the park of Vancouver City.

May 28 proved to be the red-letter day of our trip. We left our camp at Brat River at. four in the morning and had not travelled a mile before we spied a heavy black bear on the east side of the inlet, feeding amidst thick cottonwood brush within a hundred yards of the water.

Prom our point of view he could not have chosen a better position. The wind blew steadily in our faces; above where he was feeding impassable crags towered away up to snow line; down wind his retreat was cut off by a precipice, and when we had hastily blocked his only outlet on the up- wind side we realized he was bound to afford a shot.

It was, however, a dangerous maneuver to give him our wind before the canoe reached shore, but we were ready directly the keel grounded, and were up the hill before the bear realized his awkward predicament. He was probably only just out of his winter quarters, for he sulked in the bushes out of sight. I motioned Frank to stir him up, and waited by the trunk of a dead tree, where a narrow game trail led through the brush in his direction. Prom this position I moved forward to a point where the game trail crossed a narrow cleft in the steep hillside, offering perhaps fifteen or twenty yards’ clear view ahead.

Through the tops of the pine trees on the left. one could see the silvery glimmer of the sea below, and on the right the vast, precipitous rock wall towered upwards into the clear blue sky.

Every sense was naturally on the alert at the proximity of the bear, but the denouement was certainly unexpected. I heard Prank’s excited yell from above me : “Look out, below them!” There was only one possible way to look, and that was along the game trail, but I certainly never expected to see that great brute suddenly appear on the very path on which I myself was standing, lees than fifteen yards away.

If he had not received a bullet in his great chest almost the instant be appeared in sight he would have undoubtedly pushed me off the trail. At the shot he fell sideways downhill and a second shot through the neck effectually settled him.

This was the largest black bear killed up Gardner Inlet last season, a very fine male in perfect coat.

Even the Indians, who speak of a skin with the critical eyes of the fur trader, view obliged to confess this great bear was one of the best. they had ever seen. It took three of as to lift him out of the wedge into which he had Wien sad pall him downhill towards the canoe.

We had now heavy bears on board, the female of the previous night and the one just killed, so we hoisted the spritsail and made short tracks to a length of sandy beach, where the warm sun offered a congenial point for the operation of skinning.

At this particular point. Gardner Inlet takes a complete rectangular bend, its course changing from a direct N.E. by E. to ono in an alitio.t contrary direction.

This huge bend forms a sheltered bay on the eastern side, where the sun had evidently melted the snow earlier than usual, and the resulting avalanches haul left a succession of bare slides stretching from the water’s edge for a mile up to the snow line.

Every inch of this grand country needed careful spying, nor were we long in finding what we were in search of. David, whose keen eyes were glued to the rock walls immediately below the snow, was the first to sight him, a great brown fellow, though whether a grizzly or not we were unable to determine at the distance.

The country was more or less open, with here and there clumps of stunted trees in the centre of glades devoid of underbrush, while the wind-swept slides were completely bare of cover.

My companion and his guide were soon away uphill after this bear, and for a time we lost sight of the two men amidst a thicket of cottonwoods.

When we next saw them, they were- within a hundred yards of the unsuspecting bear, and we could see the glimmer of the rifle barrel in the sun.

With the report of the shots the bear galloped away but had not run a hundred yards before he rolled over among the rocks, and we soon scrambled up to him.

He proved to be a remarkably fine brown or cinnamon bear, only a few inches shorter than our last black one, with a coat of almost chestnut hue, thick and glory.

My companion, who has probably killed more bears than any other non-professional hunter in British Columbia, was justly proud of the beast.

We had now three bears to engage our attention for the next few hours, and while three of us set to work skinning David prepared a savoury meal.

It took us until three in the afternoon to clean and stretch the skins, when suddenly Frank exclaimed, Look there!” We all sprang to our feet and followed the direction of his outstretched hand.

There, less than half a mile uphill, fast asleep on a huge, isolated boulder, lay a great black bear. Incredible though it may seem, we had for more than two hours cooked our food, laughed, talked, and smoked our pipes while that bear had walked up and gone to sleep practically within rifle shot. With his head resting on hiss outstretched forepaws, he was evidently oblivious of our proximity.

From where we stood the bare hillside stretched upwards to the snow line fully a mile away, and ho lay on a boulder about halfway up the slope. Frank and I had merely to change our boots for rubber-soled shoes, throw off our coats, and away up the centre of a narrow cleft filled with muddy, melting snow.

Beneath this crust of snow, a noisy little stream dashed downwards in a series of waterfalls to the sea below, effectually drowning any noise from our footsteps, affording us a grand approach to within a hundred yards of the bear.

The wind was just right, and an easier stalk could hardly be imagined. Then we climbed up 10feet. to the lip of the gully, raised our beads cautiously, to find ourselves within fifty yards of the still sleeping animal.

One bad but to raise the rifle to a convenient position, push up the safety catch, and draw a fatal bead on his shoulder.

At the shot he fell or rolled off the rock in one frenzied dive into the thicket below, and though he wormed his way for half a mile before Frank finally gave him the coup de grace, he was obviously ours from the first.

It turned out subsequently that the first bullet, aimed for his shoulder as he lay outstretched, had struck him too low, and was within an ace of inflicting a trivial wound that would have lost him to us for ever.

Our luck for the day was now about finished, for though we sighted yet another bear on the east side just before sundown, he was too high up, and it was too dark, too late, and too dangerous to go after him.

We cruised down the Inlet for another fortnight, and saw bears in several of the subsidiary valleys, but with our great day at the Brin River our adventures were practically at an end.

We were detained by contrary winds and bad weather for another week before reaching the nearest settlement, when a south-bound steamer might be expected, and two idle days had to be wasted before a steamer of any kind came along and bore us southwards.

Looking back at the results of that trip and the number of bears seen, I am more than ever convinced of the necessity of being on the spot as early in the spring as possible, for once the leaves cover the cottonwood bushes the bears are lost in a veritable jungle.

John H Wrigley

Astonishingly The Field (no longer Field The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper) is still in existence when the digital carnage has lead to the deaths of many magazines and too many newspapers. Field was founded as a weekly in 1853 and is older than any other currently monthly British publication. It is the world’s oldest rural affairs magazine. Only one British magazine is older, the weekly The Economist (founded 1843). The Observer (founded 1791)is now the Sunday newspaper version of The Guardian.