Paul Begla, in the Huffington Post, writes Yes National Review, We did execute the Japanese for waterboarding.

Begala is responding to an assertion by Mark Hemingway of National Review Online that U.S. did not execute the Japanese.

The problem with that debate is that it is apparently based on only one case, that of Yukio Asano, and that debate is based only on the online summary of the trial. Apparently it's too much in this internet age to have a debate on the substance of a matter of national and international importance based on the facts or substantive research, just what you pick up on the web. (And these are older adults, so why are we boomers complaining about kids basing their school work on Wikipedia? We have here role models for Wiki-searching from both sides of the polarized American political spectrum.)

There is the usual American parochialism, that it only counts, apparently, if an American was waterboarded or if the Americans executed war criminals for waterboarding. To many Americans, and almost all American conservatives, not only on the Huffington Post or the National Review Online, but on other blogs, that the British tried the Japanese for waterboarding is of little or no importance.

That's why it's called International Humanitarian Law (A lot of the evidence against the Japanese for torture in the Double Tenth case, which was a British military tribunal, came from American war crimes investigators.)

Finally there's a double anonymous comment on the Huffington Post in response to Begala. From an anonymous poster calling himself The Golden Master, quoting an equally anonymous so-called close assosicate who apparently says:

In the first place, I had studied, written, and; 'published' on the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, but I've never come across information that the Japanese waterboarded their captives, even less that Japanese war criminals were executed for waterboarding. So, Paul Begala has no credibility unless he produces his source(s) for that assertion.

Obviously whomever this person is has never actually checked the index to the published edition of the transcript of the hearing of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Far East, for the "water treatment" is easy to find.

I quoted from the trial in my original post

This form of torture was not limited to Singapore. The judgment of the Tokyo war crimes trial said “the water treatment was commonly applied…there is evidence that this torture was used in the following places: (spelling in the original)

China, at Shanghai, Peiping and Nanking

French IndoChina, at Hanoi and Saigon

Malaya, a Singapore

Burma, at Kyaikto

Thailand, at Chumporn

Andaman Islands, at Port Blair

Borneo, at Jesselton

Sumatra, at Madan, Tadjong Keareng and Palembang

Java, at Batavia, Badung, Soerabaja and Buitonzorg

Celebes, at Makeskar

Portuguese Timor, at Orzu and Dilli

Philippines, at Manila, Nichols Field, Palo Beach and Dumquete

Formosa, at Camp Haito

Japan, at Tokyo"

The online debate was triggered by this "discussion" on CNN's Anderson Cooper.

There is also Andrew Sullivan's response to Hemingway here and to Begala here.

Update:

There's a good summary (and much more intelligent debate) on Mahalo Answers.

Technorati tags

writing, journalism, Burma Thailand Railway, World War II, torture,F Force, Prisoner of War,military tribunal, waterboarding, law, book, CNN, Huffington Post, National Review

Labels: A River Kwai Story, Andrew Sullivan, CNN, F Force, Geneva Convention, Guantanamo, Huffington Post, human rights, Japan, National Review, Singapore, Tokyo trial, torture, waterboarding, World War II

Although many legal experts who have been discussing the case of Blackwater USA, the private contractor now being investigated for a shootout in Baghdad, say private contractors are in legal limbo, accountable to neither government nor laws, there is yet another episode from the Second World War in the Far East that is relevant to the modern world.

The guards in the River Kwai prison camps were gonzoku, private contractors employed by the Imperial Japanese Army. Many were tried as war criminals after war, including two of the defendants in A River Kwai Story.

Link to my story for CBCnews.ca

Private military contractors subject to rule of law

Second World War gonzoku provide precedent

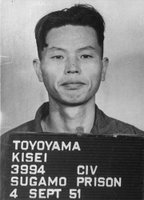

One of the main characters in A River Kwai Story is a Korean gonzoku or civilian contractor named Hong Ki-song, also known by his Japanese name Toyoyama Kisei, who was one of the most hated guards on the Burma Thailand Railway, and was notorious for beating prisoners of war with the shaft of a golf club. Toyoyama, who volunteered for the duty, was sentenced to death by a British military court in Singapore. That sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment. This mug shot was taken by the U.S. army in Sugamo Prison in Tokyo. (U.S. National Archives)

Technorati tags

writing, journalism, Burma Thailand Railway, World War II, Iraq,F Force, Prisoner of War,

military tribunal, Blackwater, law, book

Labels: A River Kwai Story, Burma Thailand Railway, CBC, F Force, human rights, war crime, World War II, writing

At the same time, the Australian publisher, Allen and Unwin, has postponed publication a second time, so instead of 2007, it is now scheduled for late April 2008, to coincide with Australia's ANZAC Day. The book had been scheduled for July 6, 2007, but there were delays in the editing process.

It appears from what I am told, that unlike in North America, where the major selling period for books is around Christmas, publishers Down Under consider Christmas to be one of the worst times to sell books, except, as I was told "children's books and large novels." I am guessing it is maybe the weather, here everyone bundles up and reads through the winter, in Australia, I guess, they all go to the beach.

Also the book will not be available on Amazon, or any other online retailer. I had hoped that I could make up for the total lack of interest by North American and British publishers with sales on the major online retailers. That apparently is not possible, since Allan and Unwin only purchased the Australia and New Zealand rights, they can't put it up on Amazon.

Now, after I get the galleys (early September I hope) perhaps my agent can kindle some interest somewhere.

One online bookstore in Queensland is advertising the book. So you can order it from QBD The Bookshop, an online bookseller in Australia, which does ship internationally. Prices are in Australian dollars.

Link to order A River Kwai Story from QBD The Bookshop

So what are my plans? This project has taken more years than I ever expected. It was in July 2000 that I was admitted to the Interdisciplinary Masters Program at York University and Osgoode Hall Law School. I defended my thesis in September 2003 and graduated in November 2003. It took me six weeks, part time, to write the thesis. But it took more than two and a half years to write the book. It took longer than I expected to turn the academic argument into a narrative. And then, as mentioned earlier in this blog, publication was postponed last year.

So I while I have a few other ideas on my hard drive, I am not going to write a word, outside of work, until the book comes out. It's time to catch up on things I have put on hold for the past seven years. Let's hope that the next seven will be good ones.

Technorati tags

writing, journalism, Burma Thailand Railway, World War II, Australia,F Force, Prisoner of War,

military tribunal,POW, book

Labels: A River Kwai Story, Allen and Unwin, Australia, Canada, CBC, human rights, writing

This just posted on CBC.ca/news

Alberto Gonzales and the Geneva Convention.

Did the president's lawyer misread the Geneva Convention?

Did Alberto Gonzales, the embattled attorney general of the United States, turn a blind eye to legal history when he wrote a memo to President George W. Bush back in 2002 suggesting ways to avoid the Geneva Convention?

Although my book, A River Kwai Story The Sonkrai Tribunal is largely about the Second World War, it is also about the Geneva Convention and the inhuman treatment of prisoners of war.

So when I was doing my research for the book and I read a key phrase in a memo written January 25, 2002, from Gonzales to President George Bush (and leaked when the Abu Ghraib scandal broke) that said.

. . . some of the language of the GPW [Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War] is undefined (it prohibits, for example, ‘outrages against personal dignity’ and ‘inhuman treatment’) . . .

I was, to say the least, surprised, since almost all the Far East war crimes trials for the abuse of prisoner of war, charged or contained the phrase "inhuman treatment."

I was, to say the least, surprised, since almost all the Far East war crimes trials for the abuse of prisoner of war, charged or contained the phrase "inhuman treatment." How could the counsel to the president of the United States ignore the suffering of several hundred thousand Allied prisoners of war, including thousands of American POWs?"

It may take many years of history to answer that question.

The CBC news story outlines what Gonzales should have known when he wrote that memo.

The book, of course, will tell the reader, the exact details of the "inhuman treatment" carried out by the Japanese against the men of F Force.

Technorati tags

CBC, journalism, Burma Thailand Railway, World War II, Australia,F Force, Prisoner of War,

military tribunal, Alberto Gonzales, POW, Geneva Convention

Labels: A River Kwai Story, Alberto Gonzales, Burma Thailand Railway, CBC, Geneva Convention, Guantanamo, human rights, Singapore, United States, war crime, World War II

The title is now

A River Kwai Story

F Force and the Sonkrai Tribunal

Labels: Burma Thailand Railway, Guantanamo, human rights, Japan, publishing, Singapore, World War II, writing

Japanese War Crimes were covered by the Nazi War Crimes Act passed by the US Congress in 1999.

As of January 12, 2007, 100,000 pages of records are now available to the public.

The Archives press release is here. www.archives.gov/press/press-releases/2007/nr07-42.html.

The page also contains pdf downloads which tells you how to research in the Archives.

The main page for the Interagency Working Group on war crimes is at

http://www.archives.gov/iwg/

Labels: archives, human rights, Japan, research, United States, war crime, water torture, World War II

Update: January 17.

Charles Stimson apologized for last week's remarks about lawyers defending terror suspects.

BBC Report

Reuters report here.

"Regrettably, my comments left the impression that I question the integrity of those engaged in the zealous defense of detainees in Guantanamo. I do not," Stimson wrote in response to the furor over his remarks.

"I apologize for what I said and to those lawyers and law firms who are representing clients at Guantanamo. I hope that my record of public service makes clear that those comments do not reflect my core beliefs," he wrote.

So why did Stimson make the remarks in the first place?

Update 2.

Harvard Law professor Charles Fried zeroed in on Charles Stimson in an op ed piece in the Wall Street Journal, now reprinted on the Harvard site.

Fried was Ronald Reagan's Solicitor General and is considered a leading U.S. conservative lawyer:

In his article, Fried says:

How unfortunate that in this country we have plaintiffs' lawyers and defendants' lawyers, lawyers who represent only unions and others who represent only management. One looks with nostalgia at the British bar, where barristers will prosecute one day and defend the next.

That's what my original post was all about.

Original post begins-and stands.

There is a little known fact in the history of war crimes.

The first British war crimes trial in the Far East after the Second World War was for Japanese crimes against Muslim prisoners of war.

Muslim prisoners of war liberated by the United States Marine Corps.

A war crimes case that was first investigated by the Marines, before it was handed on to the British.

The British made sure that the Japanese accused got a vigorous defence.

How times have changed.

Last week, the New York Times and other American media reported the shocking story of how far some in the Bush administration are willing to go in dismantling centuries of Western democratic and legal tradition.

On January 13, 2007, the Times reported that Charles Stimson, deputy assistant secretary of defense for detainee affairs had told a Washington radio station that serves employees of the American government that he "was dismayed that lawyers at many of the nation’s top firms were representing prisoners at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and that the firms’ corporate clients should consider ending their business ties."

The Wall Street Journal made the same point in an editorial which the Times says "quoted an unnamed 'senior U.S. official' as saying, 'Corporate C.E.O.’s seeing this should ask firms to choose between lucrative retainers and representing terrorists."

Here is the summary of the story from Editor & Publisher.

Here is the UPI version of the story as it appeared in the conservative Washington Times.

More on Stimson later in this post. But perhaps Stimson and the conservative radio talk show host who made a Freedom of Information request for the list of law firms should learn something from history, which brings me back to Japanese war crimes.

The Muslim prisoners were among members of the British Indian Army, from the Frontier Force Regiment and the Hyberabad Infantry,who refused to join the pro-Japanese Indian National Army after the surrender of Singapore. They were put on board a "hell ship" and sent to the island of Babelthuap in the Palau Islands where they spent three years as slave labour for the Japanese.

When it came to the trial, the British made no secret of the political reasons that the case was the first to be tried. It was aimed at the population of India, which was soon to be independent.

The case was named for the senior Japanese officer in the case Gozawa Sadaichi and nine others.

(with Gozawa, the last name first in Japanese style). You can find a summary of the case on the University of California at Berkeley war crimes site.

A young British lawyer named Colin Sleeman was one of two named to defend the 10 Japanese and two years later published an account of the trial. For this post what he says about defence in such a trial is worth remembering

To be charged with the responsibility of conducting the defence, upon capital charges, of ten nationals of a State so lately our bitterest enemy and who were facing accusations of brutality and murder against members of the British armed force was as indeed as curious a position as that in which any two British officers could find themselves placed....

How a man can defend a prisoner whom he knows or feels, to be guilty? The answer generally is (and certainly was in the Gozawa case) that he does not know. As Dr. Johnson said: "A lawyer has no business with the justice or injustice of the cause he undertakes, unless his client asks his opinion and then he is bound to give it honestly. The justice or injustice of the cause is to be decided by the Judge..."

In a criminal case then, the duty of an advocate for the accused is, regardless of his personal feelings, "to protect his client as much as possible from being convicted, except by competent tribunal and upon legal evidence sufficient to support a conviction with which he is charged."

Sleeman reported that the his clients were "extremely favourably impressed by the kind of trial which they were getting. Gozawa Sadiachi freely admitted this himself and frankly agreed that had the position been reversed, the captives would have been shot out of hand just as their Japanese captors thought fit."

Sleeman concluded his introduction to the trial with these words:

It is, I think, fairly clear that the average citizen of this country wants to see the Japanese War Criminals disposed of summarily without too much delay or fuss, but I am not sure what his attitude would be if it were fairly put to him that by doing so he would be in grave danger of doing himself one of the chief things he fought against, namely killing innocent men in the general massacre. In any case it would certainly have harmful consequences in the future. It is hoped that when the future comes, the ordinary man will be glad that he did not allow his natural feelings of indignation and horror to override his principles; for emotions are a bad guide to conduct when long-standing principles are in question.

In a second case, one I have written and blogged about before, where the Japanese waterboarded innocent British, Eurasian and Chinese civilians, Sleeman was the prosecutor; a man named Samuel Silkin defended.

The two together wrote an account of that trial and they concluded:

To many the most important question which arises out of cases such as this: What is the purpose of trying and executing those involved and what benefit is likely to be secured? That the desire for retribution is an element in the answer to this question can hardly be denied. But that is not the most important factor. Wars in themselves are inhuman, but it is possible to temper their inhumanity with the rules, which are observed by participating nations. If the Double Tenth case served no other purpose it served this, that is had been clearly placed on record that no soldier or civilian of a belligerent power can excuse his individual conduct, howsoever offensive and repugnant to civilized morality it may be, by the plead he was forced to commit it in difference to the commands of his superiors. In wartime it is easy to lose sight of the principles of individual responsibility: it is the purpose of such trials to ensure that this responsibility is fostered and remembered.

(My emphasis in both quotes)

Colin Sleeman went on to become a distinguished British judge who died in the summer of 2006. (Obituary from The Times here and The Telegraph here.)

Samuel Silkin became the Attorney General of the United Kingdom in the Labour governments from 1974-1979 and later a member of the House of Lords.

Some in the Bush administration would argue that eight centuries of legal tradition matters not because the accused are not from a belligerent power, a "participating nation."

That is wrong.

Whether or not they are uniformed members of a regular army or ununiformed guerrillas, insurgents and terrorists, the purpose of the trial, as Silkin and Sleeman pointed out, is that the law finds individual responsibility and holds those individuals to account.

And one, sadly, has to wonder if the law will ever hold to account those who are now authorizing and carrying out waterboarding in the name of freedom.

And certainly, since many prisoners at Guantanamo have been released, a good many still there could be innocent.

Sleeman was right in his stand that it is a fair trial, with a vigorous defence, that distinguishes our society from the others.

Back to Stimson.

After the Times articles, the Pentagon quickly disassociated itself from its deputy assistant secretary, as reported by an Associated Press report on the CNN website.

Blogger Andrew Sullivan has twice called for Stimson to be fired, here and here.

Sullivan says

He should be fired, if the deep damage that this administration has already done to the rule of law in America is not to be compounded.

That sounds familiar to me.

Here is what the late Lord Louis Mountbatten, then the Supreme Allied Commander in Southeast Asia, wrote in his introduction to Colin Sleeman's book on the Gozawa trial.

I considered that nothing would diminish our prestige more than if we appeared to be instigating vindictive trials against individuals of a beaten enemy nation, on charges which even our own courts found themselves unable to substantiate.

Labels: Andrew Sullivan, Charles Stimson, Guantanamo, human rights, Japan, Singapore, slavery. slave, torture, United States, war crime, water torture, waterboarding, World War II

Andrew Sullivan's Daily Dish blog continues its excellent coverage of the torture issue in the United States. In one post, "Christians for Torture" on September 21, 2006, Sullivan points to the U.S based Traditional Values Coalition and its news release on September 18, threatening to hold U.S. legislators accountable if they actually do the right thing (as they may or may not be doing with the recent compromise with the White House) and refuse to allow the Bush administration to get around the Geneva Convention.

Here is an excerpt from the news release from the TVC

TVC Chairman Rev. Louis P. Sheldon said American military and intelligence experts are hampered by a vague "outrages upon personal dignity" statement in Article Three of the Geneva Convention of 1950.

"We need to clarify this policy for treating detainees," said Rev. Sheldon. "As it stands right now, the military and intelligence experts interrogating these terrorists are in much greater danger than the terrorists. Civil suits against our military personnel are tying their hands as they try to get vital information which will save the lives of our young military people and the innocent."

"Our rules for interrogation need to catch-up with this awful new form of war that is being fought against all of us and the us and the free world. The post-World War II standards do not apply to this new war."

Let us go back to why these "postWorld War II standards" were made international law in the first place. And again, as I have earlier in this blog, I will use the Double Tenth case in Singapore as the example.

One of the civilian internees accused by the Japanese of taking part in the sabotage mission on Singapore harbour in 1943 was the Right Reverend John Leonard Wilson, Lord Archbishop of Singapore. (The Anglican bishop, Episcopalian in the United States). As I have mentioned in earlier posts [links below] the raid was actually carried out by Australian and British commandos and the civilians interned in Singapore's Changi Jail knew nothing about it. One of the tortures the Japanese use in the Double Tenth case was waterboarding. The aim was "actionable intelligence" on who blew up the ships in Singapore harbour, the method was torture and the result was a series of confessions by innocent civilians who knew nothing about the raid whatsoever.

While Bishop Wilson was not subject to "the water treatment," I am going to quote from the affidavit he swore for the Double Tenth trial. (warning this part may disturb some readers)

On arrival at Japanese Military Police Headquarters on 17th October 1943, I was placed in a cell with approximately fifteen others under conditions set out in the report [a joint report on prison conditions submitted by internees after the war-RR]. On the same night I was taken to another room for investigation and received beatings on the shoulder with a rope. On the following day (18th October) I was made to kneel with a sharp-edged piece of metal behind my knees. My hands were tied behind my back and I was roped under the knee-hole of a desk in a very painful position. Japanese soldiers stamped upon my thighs and twisted the metal behind my knees so that it cut into the flesh. I remained in this position for nine to ten hours, sometimes being interrogated, other times being left under two Japanese guards who kicked me back into position whenenver I moved to try and get release. I was then carried back to my cell, my legs being too weak to support me.

On the following day (19th October) I was again carried upstairs and tied face downwards on a table and flogged with ropes, receiving more than 200 strokes from six guards and the chief investigator, working in relays. I was carried back to the cell and remained semi-conscious for three days and unable to stand for me than three weeks....

After this long investigations took place with threats of torture and death, but no more torture took place until February 1944 and then only for half an hour. I received medical attention and dressing for wounds for more than two months. This was given by the Japanese doctor and dressed at the Military Headquarters....

I also saw many cases of brutality by the Japanese guards inflicted upon their prisoners. In one particular case, which occurred about the beginning of November 1943, I saw Dr. Stanley, who was in the cell next to mine, at the Japanese military police headquarters being repeatedly taken to and returned from the investigation room. When he was away I could hear his voice crying out in agony denying the charges made against him. Sometimes he was carried on a chair and sometimes on a stretcher but the torture continued over a period of at least two weeks. One day he returned semiconscious. A Japanese doctor was called and he was taken away on a stretcher and never returned to the cell. I was told by a Japanese interpreter that he had died.... His death was undoubtedly due to the maltreatment he received. I saw people getting thinner and thinner as a result of their ordeal and lack of food and some of them were returned to Sime Road Camp [another prison camp in Singapore-RR] either dead or dying.

At that time, the 1929 Geneva Convention only covered military personnel who were prisoners of war, and the Japanese disregarded that. It was torture cases like the Double Tenth that led to the post war Geneva Convention that covers civilians, and it is that the Bush administration apparently is trying to find a way around.

Earlier posts on the Double Tenth case

The classified blog that got it right on water torture.

Waterboarding is a war crime

(I am still studying the compromise and what experts are saying. I will post my views soon.)

Technorati tags

torture, Geneva Convention,

Christian, Andrew Sullivan,water boarding,

Japan, World War II, Singapore, Human Rights, war crimes, traditional values,

Anglican Church

Labels: Andrew Sullivan, Geneva Convention, human rights, Japan, Singapore, torture, war crime, water torture, waterboarding